Can you explain for us your project Santa Barbara and what led you to create it?

Santa Barbara is a reconstruction of my childhood memory of how my family arrived to America from the former Soviet Union. What led me to create it was learning the truth behind how my family arrived to America. I grew up understanding one version and when I was twenty-seven my mom opened up and revealed how we arrived here. My mother had placed an advertisement through a Russian agency, in search of a man who could help her come to America. The man happened to be from Santa Barbara, California – the town made famous by the soap opera we spent years watching in Russia. The drama behind that story led me to really unpack our journey to America, how it took place and why it happened the way it did. It was a way for me to process my family’s story.

Diana Markosian The Pink Robe, 2019, from Santa Barbara

The project is multidimensional in its way of story telling and in the story itself. What inspired to tell your story through these various media?

Early on in my career I had a reckoning that photography wasn't going to be the only medium I use to understand the world. Whether it was archival images, drawings, or film, I needed more to convey what it is that I was either experiencing or learning. This project lent itself to motion just because of the nature of the soap opera Santa Barbara that inspired my family to come to America. It was also so complex and layered. I needed another medium to explore, direct and convert something that I was coming to terms with myself.

Diana Markosian, The Wedding 2019, from Santa Barbara Diana Markosian, Eli's House, 2019, from Santa Barbara

This is such a personal story, but it also speaks to larger shared cultural and political histories. How do you see your personal story within a larger context, and how do you balance this telling of micro and macro histories in Santa Barbara?

I don't see Santa Barbara as just a personal story. It’s a story of immigration, the relationship between a mother-daughter, and the larger story of the American Dream. I think the film evokes the pain that my mom and I had when I was a kid and today. It’s something that I'm very honest about because in America there’s this tendency to have this manicured family story and and I've come to accept that this isn't my story. There’s so much grey here and it’s painful, and tragic, but it’s also beautiful and real.

Diana Markosian, The Dissapointment, 2019, from Santa Barbara

This story is set in Russia after the Soviet Union collapse, and the majority of people were reduced to poverty, including my family. My parents were both Ph.Ds, and found themselves selling homemade Barbie dresses, and painting nesting dolls for tourists on the Red Square. My parents eventually separated, and my mother fled to America, while my father stayed behind, and didn't have contact with us for 15 years.

Diana Markosian, Moscow Breadline, 2019, from Santa Barbara

The challenge is how to communicate the complexity of a story as an artist. How do I bring to life an event that happened twenty years ago? That process excites me as an artist, as I am experimenting and learning to challenge my own understanding of image making.

Diana Markosian, My Father on My Birthday, 2019, from Santa Barbara

Diana Markosian, Lifeline, 2019, from Santa Barbara

How did you choose the moments to recapture? For example, were they sourced from personal memories?

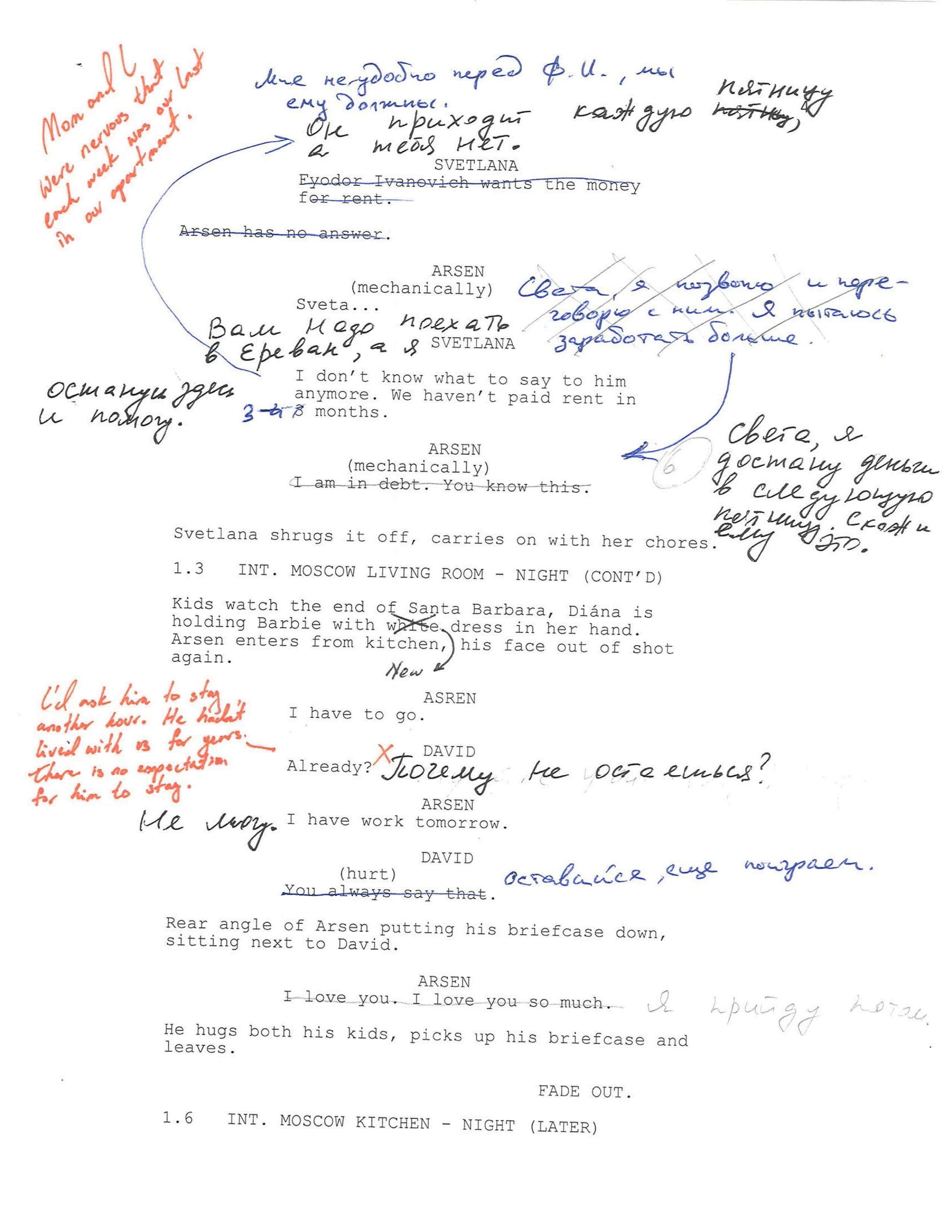

The process of creating these images felt organic. I interviewed everyone in my family early on, and found that they all had a different version of what happened. That became fascinating to me. I realized that truth and memory are so subjective. It led me to eventually collaborate with the original writer of the soap opera Santa Barbara to create my own screenplay, and I allowed everyone in my family edit the storyline to reflect their truth. Each person edited the script to reflect what happened to them, and this served as the starting point to create this project.

When I understood that nobody really had the right version — that the right version didn’t even exist — I understood that I could lean towards fiction. My goal with this project was not to throw out objectivity or completely abandon the idea of the truth; rather, I realized that truth and our memory are so subjective. The moment you go down the path of remembering, you start to understand how much you can lean towards imagination to understand an experience.

How was the experience of casting actors to play your family members?

When I started auditioning women to play my mother, I didn't necessarily understand that it would be like finding a soulmate: impossible. On one level it felt like I was replacing my own mother and on another level I felt that nobody could understand what my mother had gone through and her sacrifices.

When we searched in America, I saw more than three hundred women to play my mother. Then, I went to Russia, Armenia, and eventually to Georgia, where I met Ana Imndaze. In her audition, she played out the arrival at the airport and my first response: “How do I meet her?” I was in Wales, traveling to Berlin for a shoot and I flew to Georgia. I had less than 24 hours in Tbilisi. Initially, when I saw her, she looked nothing like my mom, yet there was something in me that said just go for it. In the year that we worked together, I saw Ana transform. She was no longer an actress. She became Svetlana. There were moments when I would ask Ana to pose a certain way, or to dress differently, and she would disagree with me. “Svetlana would never do this.” She had studied my mother’s images and mannerisms, so meticulously, to the point that she embodied Svetlana, and understood her better than me.

You commissioned Lynda Myles, the writer of the soap opera Santa Barbara, to write a script for the project, which is now published in your Aperture monograph. Why did you choose to commission this script and how did it affect your process and the way you viewed your own story?

I chose to work with Lynda because I needed a way to process this event. It felt so surreal and painful to unpack that it almost needed to become a piece of fiction in order for me to fully distance myself and experience it as someone else’s story.

Diana Markosian, Mom by the Pool, 2019, from Santa Barbara

I don't think that was the most successful, to be honest, because when we started creating these sets and began auditioning people to play my family members, it just started to become so real that every attempt to distance myself was unsuccessful. It was raw, in a way I never expected.

How do you see your work as a document or in relation to documentary photography?

I think documentary photography is shifting. The idea that we are objectively recording an event doesn’t exist anymore. Of course I believe in creating a record, but I am interested in finding new ways of doing so, because once you expand your language, you start seeing how much more there is to a story beyond an image.

Diana Markosian, The Arrival, 2019, from Santa Barbara

The COVID-19 pandemic had forced your shows to postpone. Could you describe how you plan to exhibit your work when the shows open in the future?

In an odd way, this year has been a gift to this project. I've had time to work on the film, and to really craft it in a way I couldn't before. With the pandemic, the book was delayed and shows have been postponed. We are now opening at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in February and then at the International Center of Photography in September. With the exhibition, I wanted to create an immersive experience, where the viewer begins by entering the Moscow apartment, followed by the arrival to America, and the eventual betrayal. The fourth wall is revealed behind the main exhibition with the portraits from the audition process, and finally the film, which supplements the images.

Diana Markosian, Svetlana on Set, 2018, from Santa Barbara

Diana Markosian, Santa Barbara Trailer from ROSEGALLERY on Vimeo.

Diana Markosian is known for her intimate approach to storytelling, using photography and video. Her projects have taken her to some of the most remote corners of the world, where she has created work that is both conceptual and documentary. Her images can be found in publications like National Geographic Magazine, The New Yorker and The New York Times. She holds a Masters of Science from Columbia University in New York.

Interview by Zoe Lemelson.