Can you talk about a few works in your collection that have had a big impact on you? What drew you towards them and how do they continue to inspire you?

I think I’ll start with one of the earliest photographs I ever bought: a photograph by Brassaï of a regatta on the Seine River with sailors sitting on the banks of the river. It’s a 1930s print that I acquired around 1987, and it currently hangs in my bedroom.

Brassaï, Regatta sur la Seine, 1933

Another work that I really am drawn to — and has increasing relevance — would be the work of Hank Willis Thomas. I collected so much of his work very early in his career. His work is so powerful because it is at the intersection of race and consumerism and how, in particular, the Black male is presented in media.

Hank Willis Thomas, Priceless #1, 2004

Hank Willis Thomas, Branded Head, 2003

The work that I probably am thinking of most (there are two) is Priceless, which is a riff on a Mastercard advertisement. In the advertisements, usually people are out having a good time at dinner and it lists the costs to your credit card. In this work, it shows an African American family at a graveside burial and it talks about the elements you see and don't see, like the gun and bullet. In the scene, the family is present to bury someone killed by, presumably, a fellow African American and the tragedy there.

In another series, Willis Thomas photographs a Black man’s head and torso with the Nike swoosh imposed on it — in the way that slaves were branded like cattle. It’s a very interesting statement about slavery, brands and ownership, and how Nike and other companies, brands and their consumers sort of own the Black male.

The third I will mention is the work of Philip Trager, who is in my mind an architectural photographer. I saw a show of his photographs of the villas of Palladio outside of Venice and Vicenza, Italy and I acquired the photograph that is on the cover of his book. It’s just a beautiful photograph of the 16th century villa on top of the hill. I like to collect photographs of architecture as well as men working and playing. Primarily that’s what I collect, so those three works set the tone for my collection.

Philip Trager, from Villas of Palladio

What drew you to collecting photography in particular? What interests you about photography?

Today everybody is a photographer. Before the ubiquity of cell phone cameras, I started taking photographs at an early age with a real 35 mm camera. I took a photography course in high school, and it drew me in because I am an acquisitive person in the sense that I like to acquire things, and one way you acquire something is to capture it. What drew me to collecting photography is that just as I tried to play the saxophone and was not good at it and thus greatly admire saxophonists who play well, I’m drawn to photographers that make great photographs. I am a better photographer than I am a saxophone player. I am drawn to photographers who make great photographs I wish I had taken.

The other thing is that photography has always been more accessible. It has always been and probably always will be more affordable to acquire a museum-worthy photograph than a museum-worthy painting. Also, typically photographs are very accessible to understand; they take you into a world that you've been to and they are captured better than you could have. I'm drawn to that and I respond by wanting to own the photograph.

Is there a particular artist who fascinates you right now?

I would answer that in maybe a few ways. I am addicted to Instagram because it is text and photography. It's where I live in my leisure. I recently came across the work of John Edmonds.

John Edmonds, Untitled (Du-Rag 3), 2017

His images are so interesting to me because he celebrates something that is in some communities rather commonplace: he photographs Black men wearing du-rags. It’s this thing that Black men wear, celebrate, get teased about, and it gets derided by others, and in his images he elevates the du-rag. You see the back of the male head and neckline with a blue silk du-rag. I never thought to photograph it as an object of beauty, even though I've always found them to be beautiful. I was not surprised to learn that John is Black and gay and works out of New York and went to Yale.

So, I think I'm going to like him when I meet him and I'm certainly going to enjoy acquiring his work because he seems to me to be an alter ego of mine. I am Black, I'm gay, and I went to Yale Law School. He went to Yale for Fine Arts and is involved in the whole New York art scene. I lived in New York and had a Wall Street law practice. This was the road not taken. I'm very drawn to the sort of alternative life that he represents that could have been my life and I can access that by supporting his work. He is at an intersection — again, like Hank Willis Thomas — of race and identity, sexuality, focused on the Black male, which isn’t often done enough, but when it is I do find it compelling.

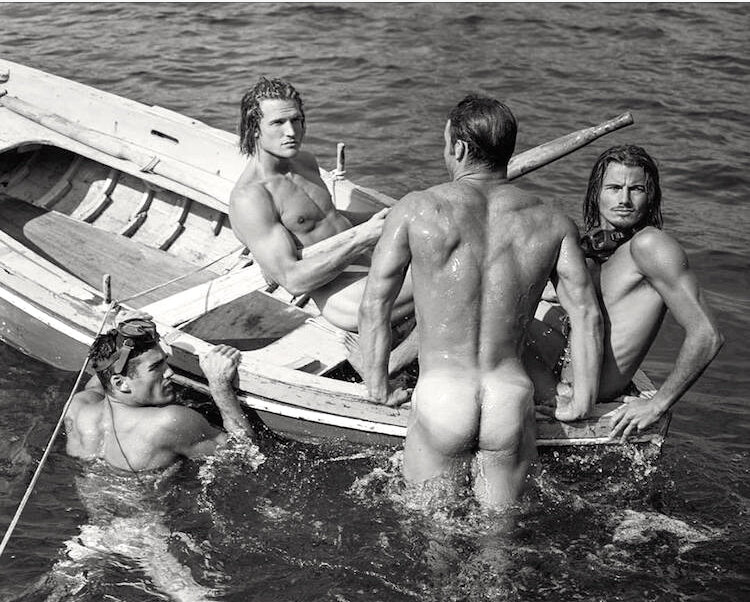

Bruce Weber, Capri, 1994

Other artists that are on my radar to collect are Bruce Weber, William Eggleston, Malick Sidibé and Robert Mapplethorpe.

No one photographs the white American male as well as Bruce Weber and my only problem is that I’m just trying to figure out which one to acquire because there are so many great images.

William Eggleston, Sumner, Mississippi, c. 1972

I'm drawn to how William Eggleston has captured the romance, color, and charm of the South. I'm from North Carolina and when I see a table setting that he's photographed it takes me back to my own childhood — some idealized version of that childhood.

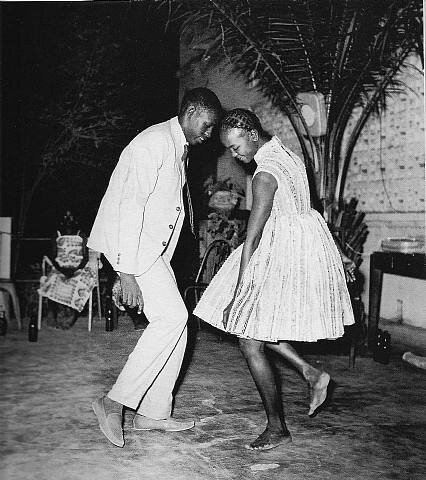

Malick Sidibé is so joyful in how he captures his fellow Africans in the 60s and the euphoria you see coming out of what I imagine was the decolonization and the heaviness of that period. People are just dancing and having fun and I keep coming back to his work again and again.

Malick Sidibé, Nuit de Noél (Happy Club), 1963

Lastly, I really want to get a Robert Mapplethorpe because of what he stands for. When I was coming out, his photography was being both celebrated and denounced. Museum shows were planned and then cancelled because politicians were threatening to withhold funding from national arts programs that supported his work because of his very explicit depictions, in particular of the Black male. My own sexuality is linked with that time period and his struggles to have his work respected and celebrated, so I want ultimately to have one of his photographs for that reason.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Ajitto, 1981

After the protests following George Floyd's murder erupted, have certain conversations about race and justice compelled you to reflect on your collection and/or collecting in general? If so, how?

The first thing being called into question is what one should do with one’s resources. You wonder if the money spent — which by some measures is not a lot and by other measures is, all because of who you ask — would be better spent dealing with social justice? Should I now sell the photographs that I have and contribute those funds to social justice? Agnes Gund, an heiress and art collector and patron of the arts in New York, sold a painting I think for 150/200 million dollars and then started a foundation for social justice. If I sold everything, then paid taxes, I could give some money to one of these causes. That’s the first thing I thought to do: liquidate and donate.

What I have decided, however, is to have my acquisitions more directed at supporting artists who are underrepresented, whose works deal with illuminating issues, whether it is police brutality, social justice or economic inequalities. Then, when my end is near, I could instruct that my photographs be sold and the money be given to an organization.

There is currently a lot of attention on art institutions and the racism and bias within and perpetuated by museum culture and structures. For example, there was a public letter recently addressed to The Getty Museum, denouncing racist and exclusionary practices perpetuated by the institution. What are your thoughts on a museum's role in creating accessible environments? How does a collector play a role in this, too?

Well, I have read the open letter to the Getty and I have read the response back. To me, it seems that what needs to be done is simple. If you look at what I understand to be the mission of the Getty: to advance and to share the world’s visual art for the benefit of all; then, it is clear that the Getty has failed at its mission. If that is indeed its mission.

I think that the Getty needs to be more inclusive in what is the world’s visual art and what that means. Further, when they say, “For the benefit of all,” I would want to see more of an effort to really have an inclusive collection, an inclusive display for special exhibitions, and for it to be truly to the benefit of all. The architecture and the fact that its up on the hill doesn't lend itself easily to access. The Getty can certainly afford to have satellite Gettys that are in underserved communities and it can do more outreach to get people from those underserved communities into this big house on the hill.

Then I think the role of collectors would be to use their membership — depending on how powerful they are in terms of their contributions and their influence — to use that influence to try to make good on what I just said. The other thing is that I could always buy something and donate it to the Getty, assuming the Getty is open to it. But the Getty has a much larger acquisition budget than I could even dream of, so it could move the needle faster and further than I could. Nonetheless, each individual collector can do something to change the complexion of the collection by acquiring and donating more works by artists of color.

If all museums were to open tomorrow (covid-free), what would be an exhibition you would like to see?

I would like to see at the Getty a show of protest photographs from the 1960s that helped drive change in America: photographs that show the impact of racism on ordinary citizens, police brutality and the defiance, and the hope that comes from the pictures of the March on Washington. In concert, I would like to see a show of photographs that were taken this spring by emerging and established photographers. It is important to make visible the horrors of racism that still exist and how things have changed. Veterans of protests, like John Lewis, have spoken about how the movement is now much more inclusive and interracial.

Bruce Davidson, Untitled from Time of Change, c. 1963

Alexander Brinitzer, New York City, June 2020

To see how it has changed — even though you still see the horrors of the clashes, whether its in Portland or LA, between the police and the protesters — would be just so powerful. It is both disappointing that there is still need for protests so many years later, but ultimately I am hopeful and optimistic because there are so many people taking to the streets who are trying to bring about change. It worked before to move the needle and hopefully will work again.

Al Perry is a North Carolina native who graduated from UNC-Chapel as a Morehead Scholar and Yale Law School. He spent six years working as a Wall Street lawyer before moving to Los Angeles to become a screenwriter. He hasn’t sold a screenplay but he keeps writing and has written “In the Bathroom”, a short which was produced, and produced and directed “The Misadventures of Barbara Wachstein, a short doc. When he isn’t working as a tv network exec, Al travels extensively internationally.

Interview by Zoe Lemelson.