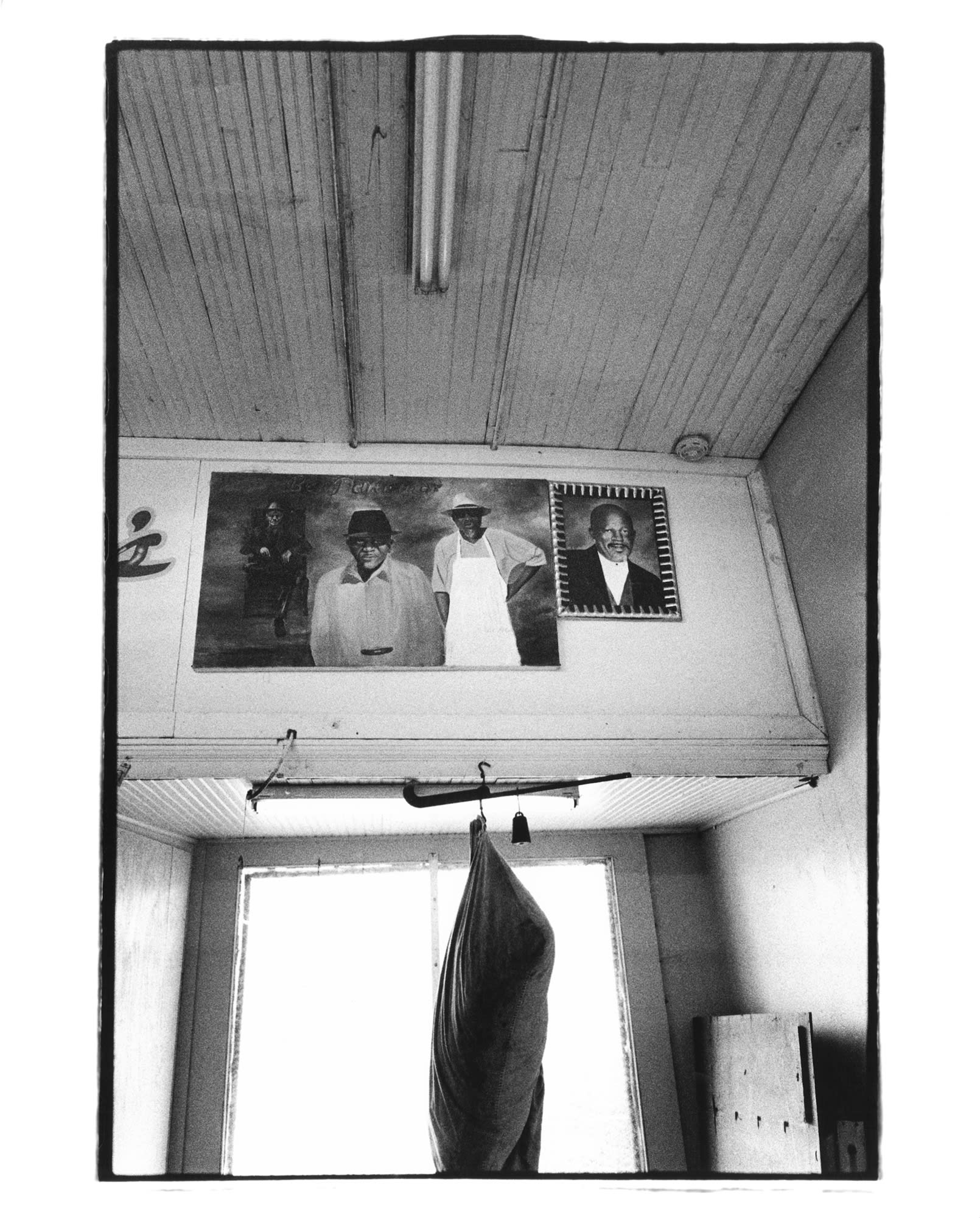

I would like to begin our conversation with a photograph you took in Mississippi of an interior space with portraits hanging on a wall just above a window, as it portends a feeling of vacancy throughout the spaces you photograph. Highway 61 exudes a sense of this region’s rich history, present through its very absence; the emptiness of rooms, landscapes, and storefronts describes a sense of loss along Highway 61. How do you perceive Highway 61 as it has changed throughout your life, and how do attempt to capture this history in your photographs?

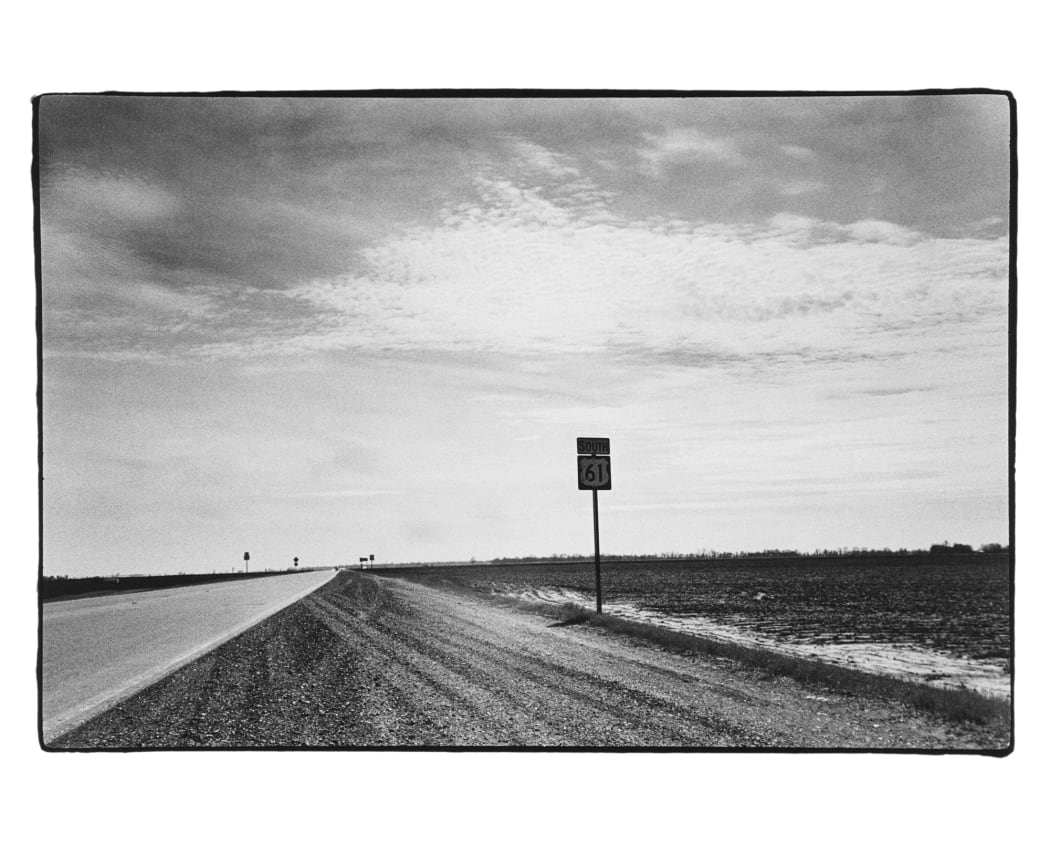

That photograph was taken in the Delta, somewhere near Clarksdale. There is a sense of loneliness all the way down that highway: not just through the Delta but from the very far north, all the way until you arrive in New Orleans.

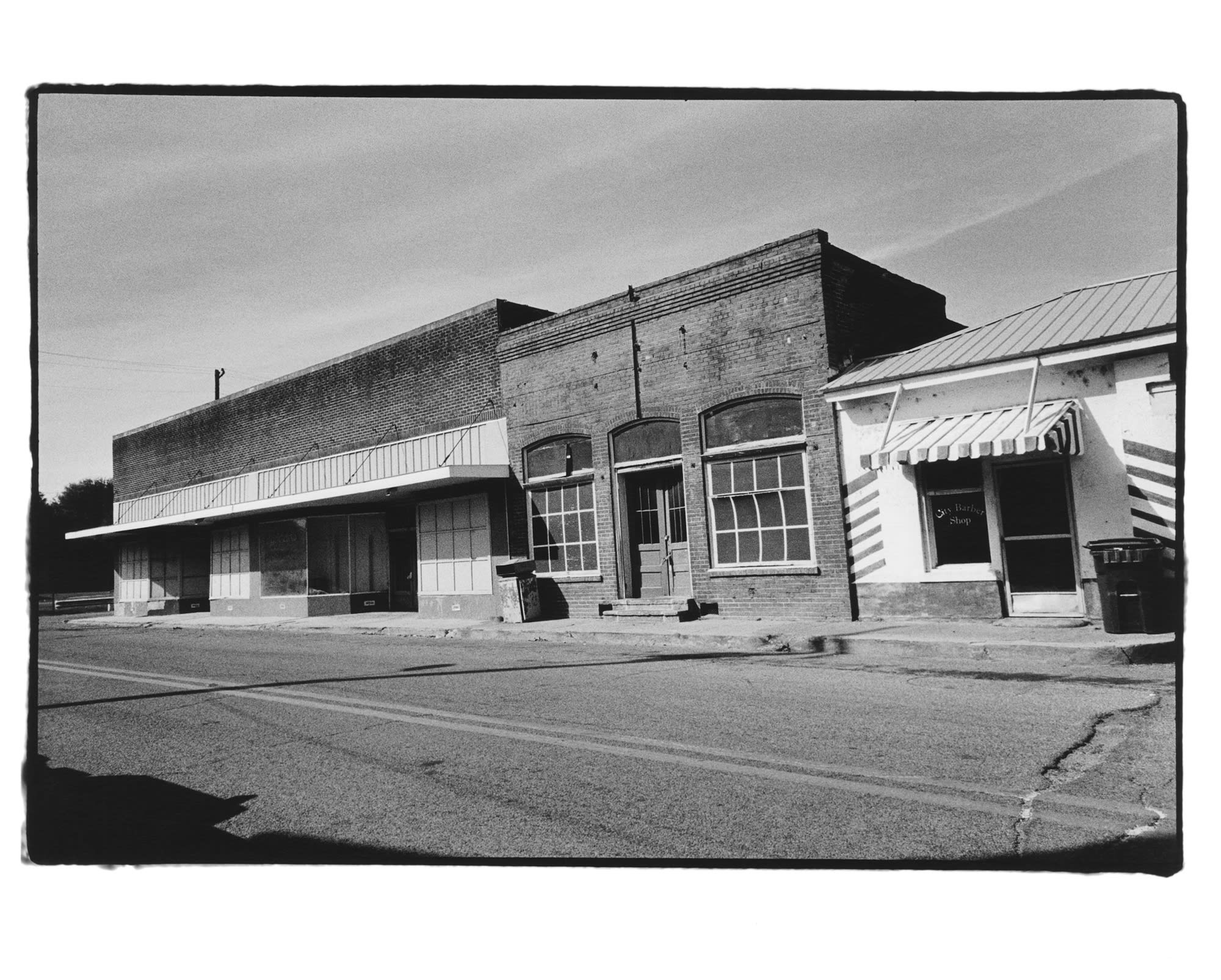

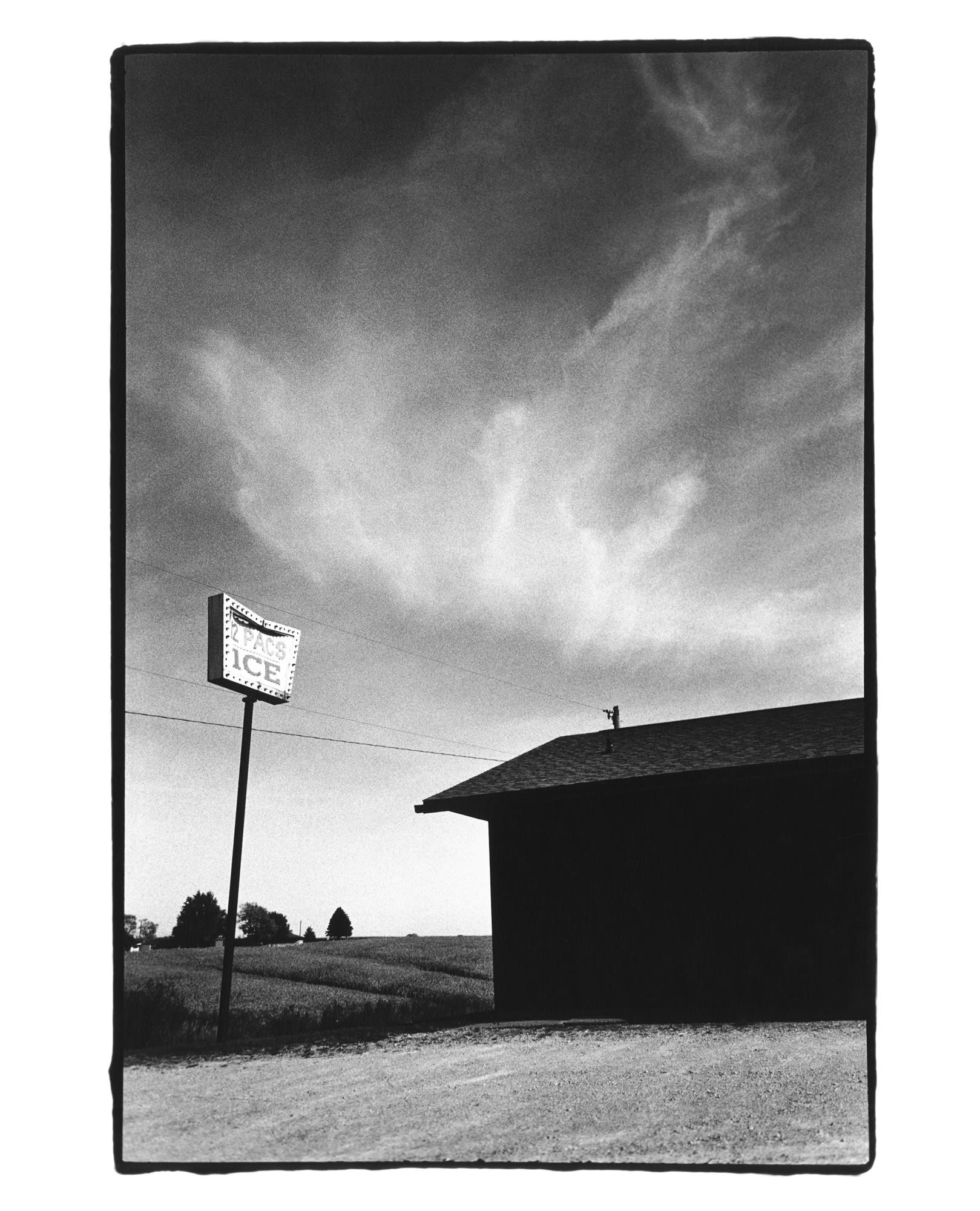

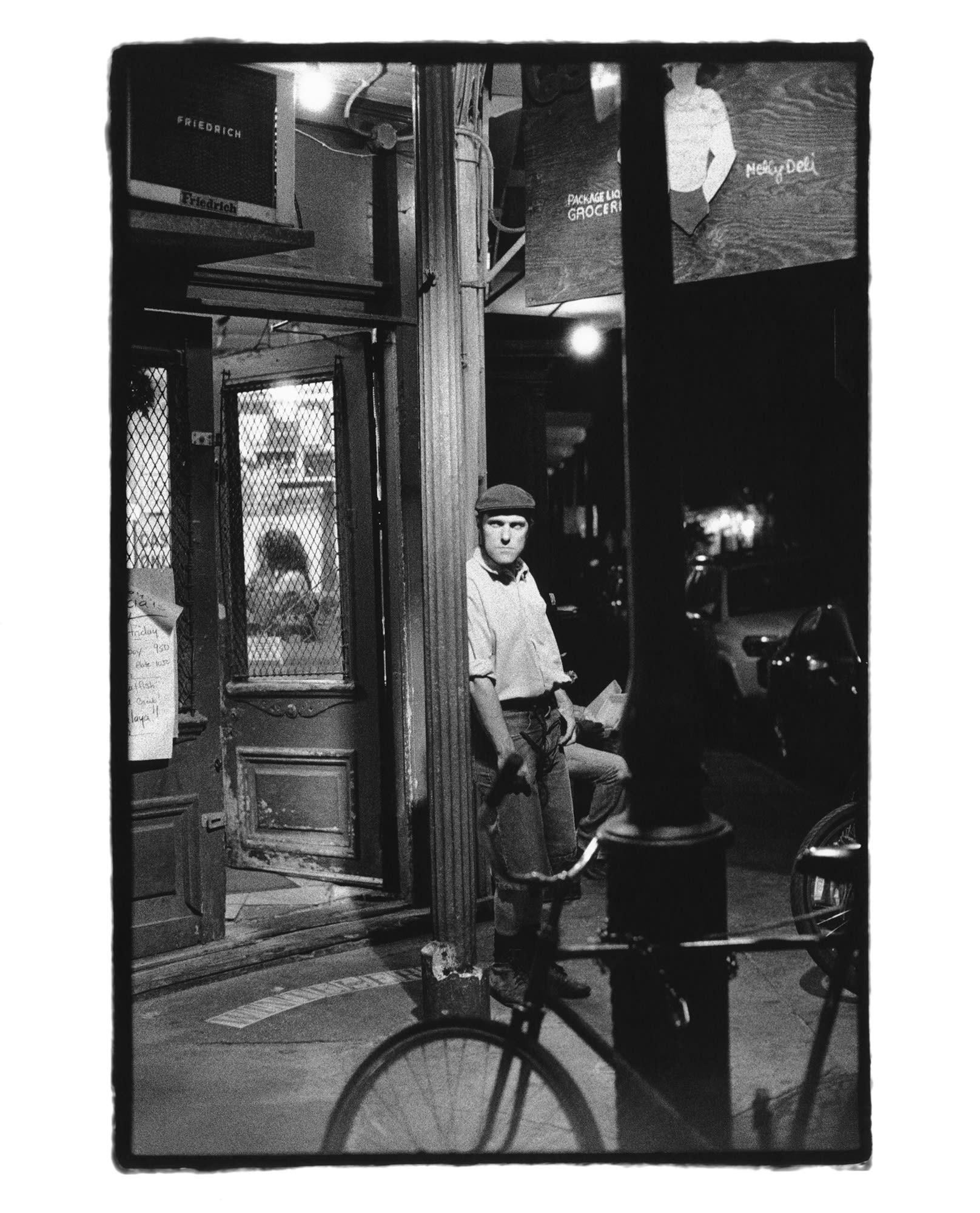

In the Delta — where that photograph is taken — and in the farm country up through southern Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas, when family farms and small farming were replaced by industrial farming, it changed everything. When farming became industrialized and owned by corporations, not only did families move off the land, but also the small rural towns that used to be the center of the farming areas began to empty out. So, you feel this absence all the way down, where things have just gone missing: the life of a community, the people who made their homes there. From what I have observed, there’s a real sense of loss more than anything all the way along.

It is also the nature of photography that you are witness to something: a moment, a place, or a time that has already passed. In the book I am photographing something that is lost.

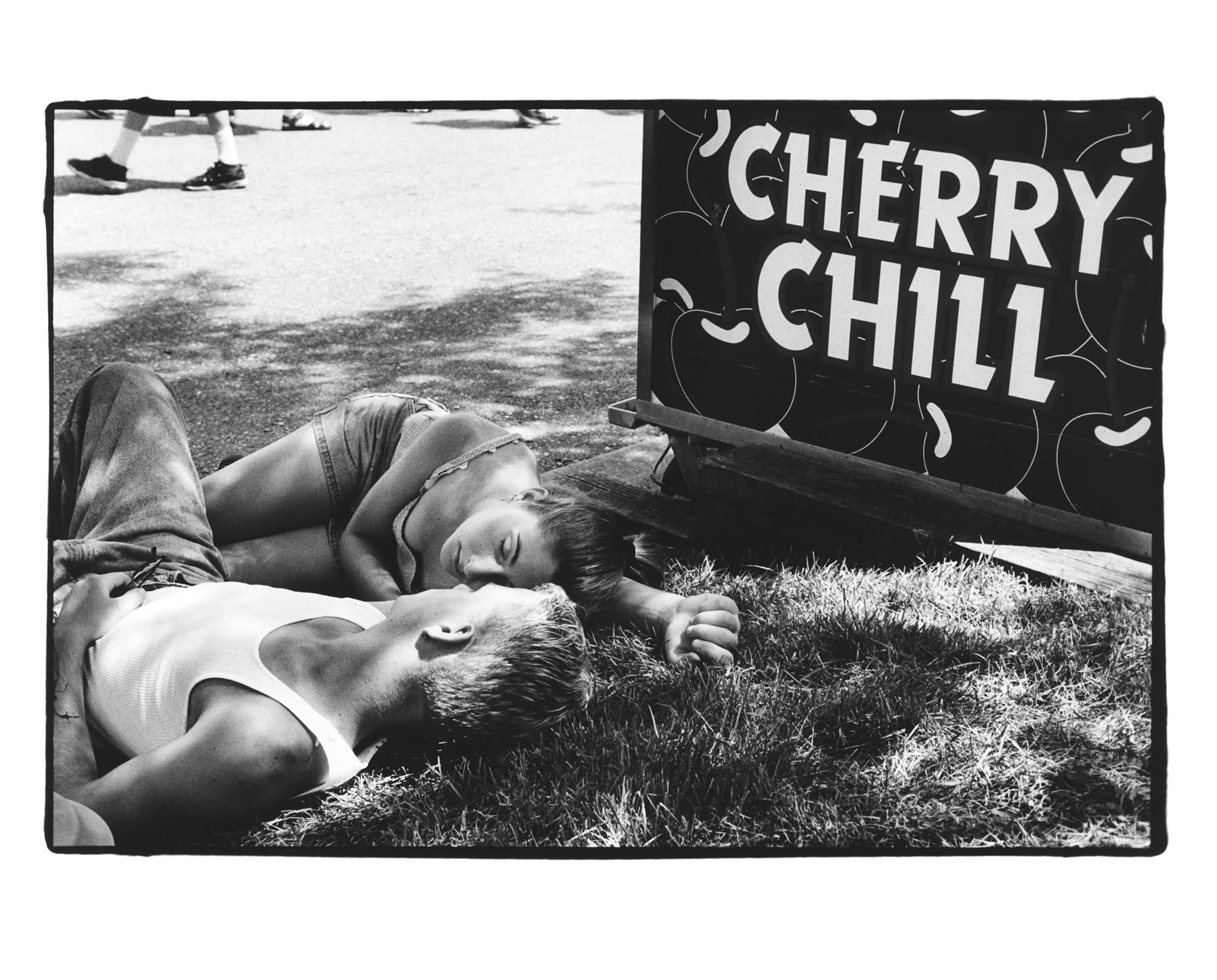

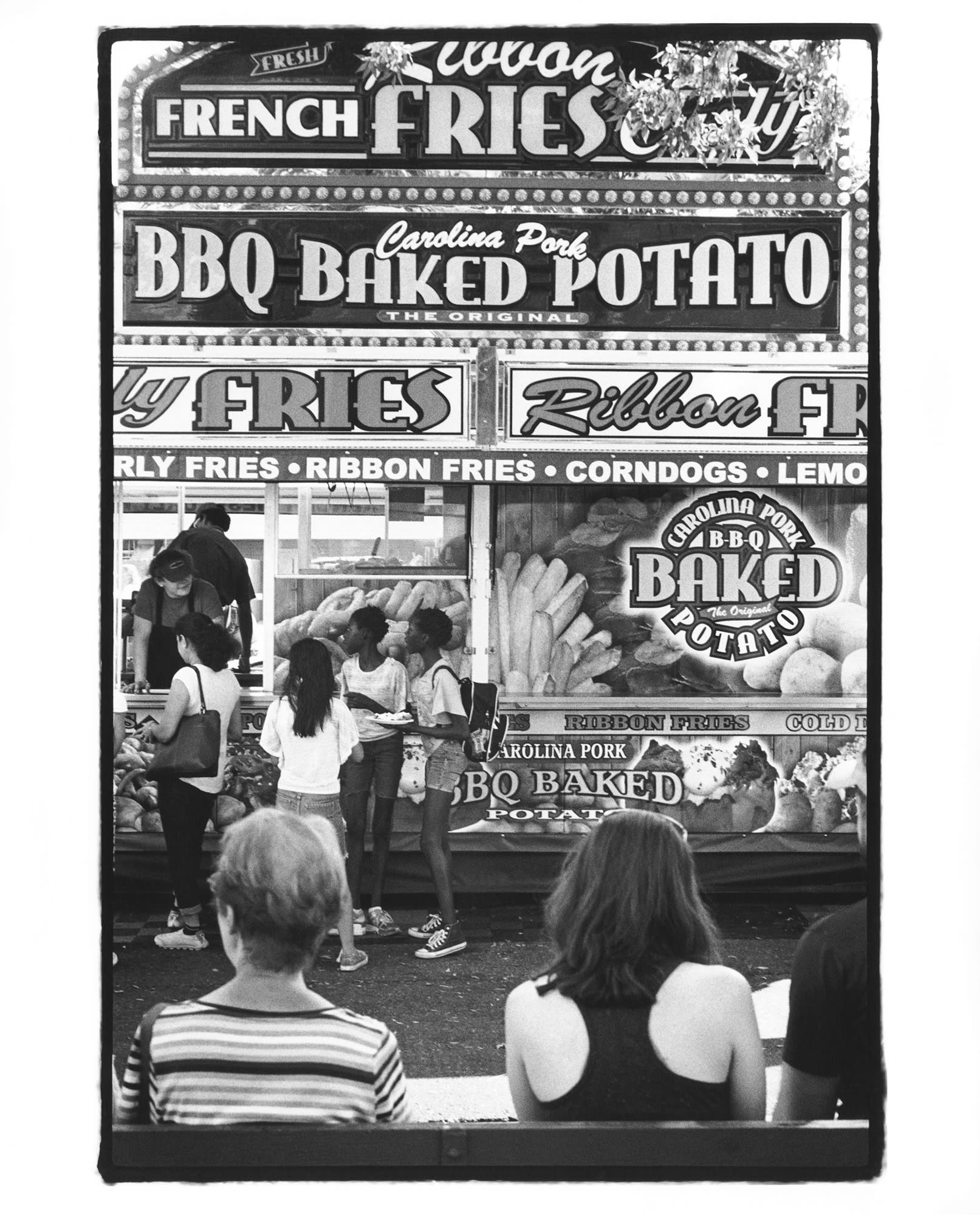

As far as changing through my lifetime, obviously I only knew the most northern part when I was a child because that was the road I grew up on. My grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins all lived in little towns along there. We drove that road to go to relatives’ homes, to the county fair or to parades and, even after I left home and went to college, that was the road I would hitchhike from the University of Minnesota back up to my family’s home. When I left for Europe for the very first time, never really to return, I caught a greyhound bus and rode out of town on that highway. Then, which is a long time ago now, it still was very vital. There were communities, main streets full of shops and people. The life that was lived in these places is gone now.

When I look at your work with the knowledge that many of these photographs were taken in the past decade, I feel almost a cognitive dissonance: I feel as if I'm already in the future, looking back at the present day as if it were the past. There is a certain timelessness, or perhaps nostalgia, in how you photograph. Do you feel a sense of nostalgia when you look at your images? What emotions are evoked in you as your look at the body of work as a whole?

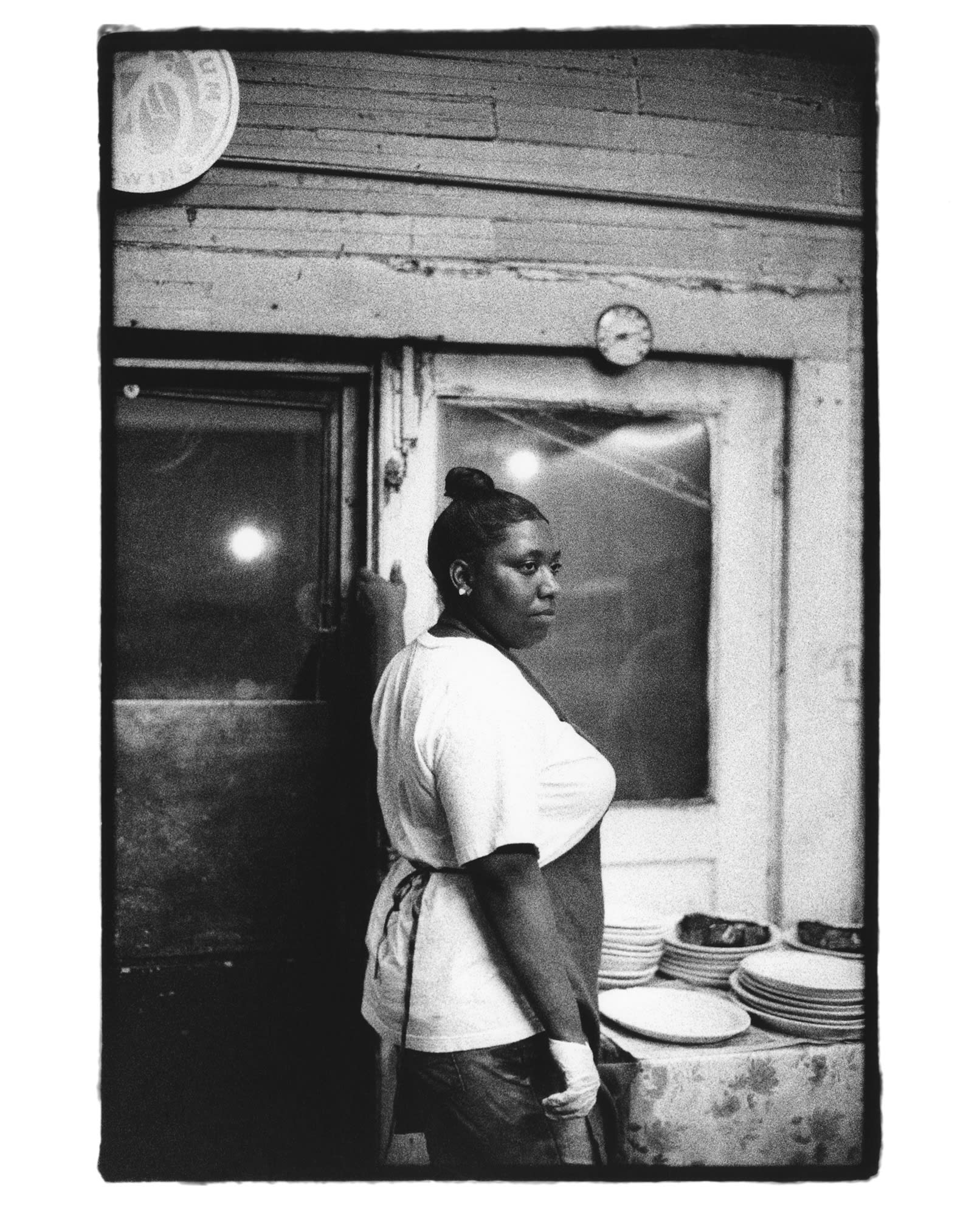

I don’t think it is nostalgia. If it were a feeling, it would definitely be a sense of loneliness and yearning. Of course, photography is completely subjective and absolutely personal. It’s the moment you raise your camera to your eye and how you respond emotionally to what you are seeing. I was drawn to those people, those places, and to those interiors. So, when I say loneliness and yearning, it is because those are two emotions that I deal with all the time in my own life and it is what I am attracted to when I see it in the world around me.

I am drawn to the poetry and the beauty of what’s been lost and, in this case, the leave-taking. Missing what is no longer there. But, I think, the main emotion for me would certainly be the loneliness.

I am drawn to the poetry and the beauty of what’s been lost and, in this case, the leave-taking. Missing what is no longer there. But, I think, the main emotion for me would certainly be the loneliness.

Highway 61 follows a meridian of energy that is incredibly powerful. In Missouri, for instance, it crosses the Trail of Tears. It does not get any more tragic than that. Also, if you listen to the lyrics of the blues songs written about Highway 61, so much is about loneliness and heartbreak. I’m sure a lot of that had to do with the migration of people leaving home, uprooting and going north.

When you photograph, are you usually alone or do you travel with company? Is your process any different if you travel with company or when you are on your own?

Well, I prefer always to photograph alone because in a way it is almost like a meditation. It’s a very private endeavor, a private exercise. When you travel with somebody, there’s always a kind of anticipation, or a hesitation to stop. Whereas, if you’re on your own, you are just wandering and you don’t have to be accountable to anybody or anything.

The photographs in your book are sequenced geographically, almost as if the reader is driving south on Highway 61 with you. How do you feel the photographs’ sequencing augments one’s understanding of this region?

It really is meant to be a road trip in the classic sense. I did want to approach it like a writer, so the images were stories I was telling on the road trip. To me, it was obvious the sequence would travel north to south.

Often, Highway 61 follows along the Mississippi River, which flows north to south. Driving south just felt like the natural flow of water.

Your photographs are very reminiscent of the work of Walker Evans and Robert Frank. Knowing that you personally knew Robert Frank, did he ever impart any lessons that you take with you as you photograph? Are there other photographers whose work inspires you, as well?

I knew Robert briefly in the late 60s and early 70s because we were living in the same loft building down on the Bowery. At the time I was not actively engaged in photography, so I wasn’t looking for any kind of guidance.

As per the other part the question of who else has influenced me, obviously Walker Evans; he was one of the first photographers I fell in love with. And, of course, Robert Frank’s work too. Josef Koudelka has been a huge influence, as has Henri Cartier-Bresson and Manuel Bravo. In my living room, I look around and see a wall of Koudelkas and a wall of Bravos, of Walker Evans, of Cartier-Bresson. These are the photographers I live with every day. They are constantly in my line of vision and in my consciousness and even if I’m not studying the work intentionally, everything about their presence in my home influences me and my work.

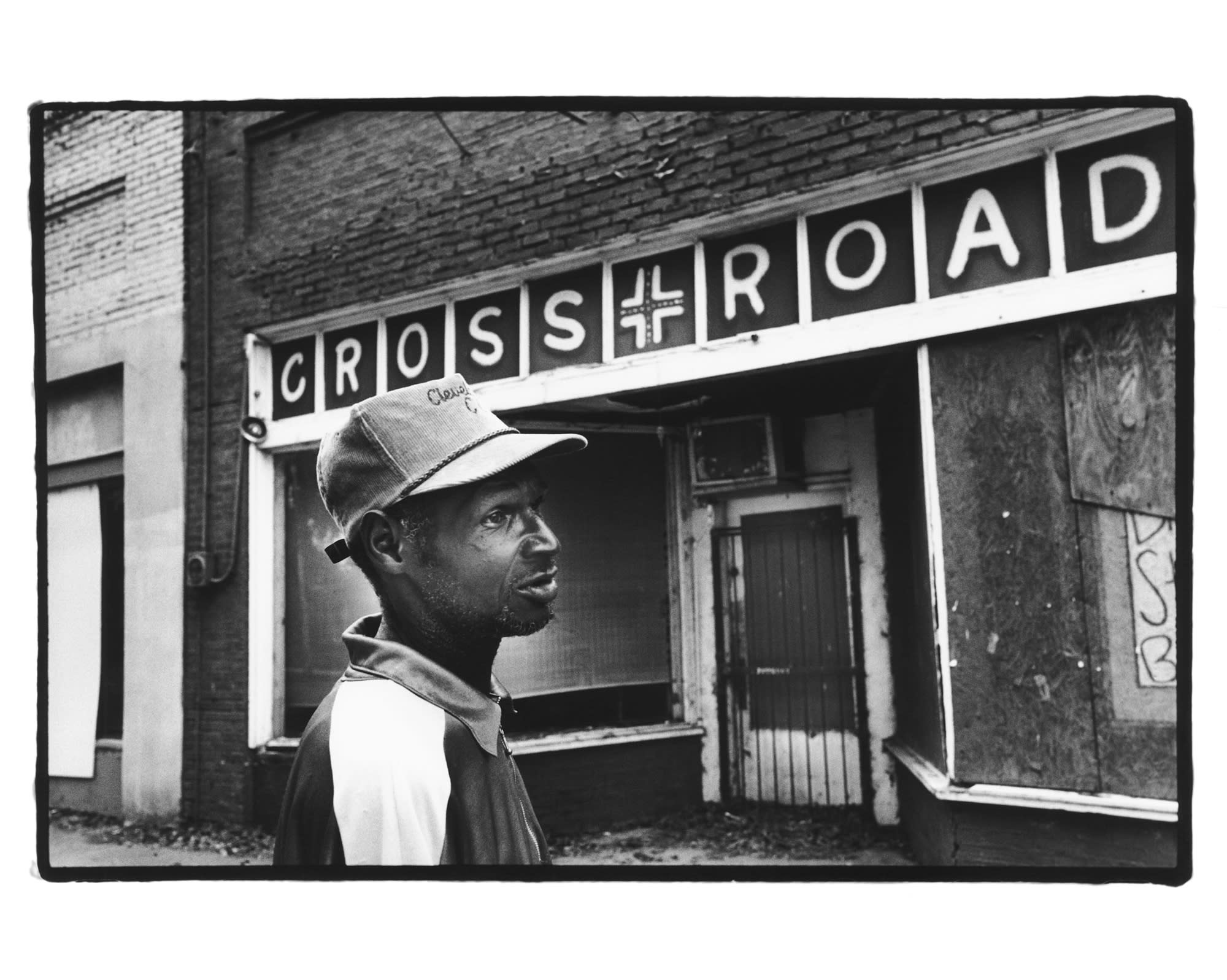

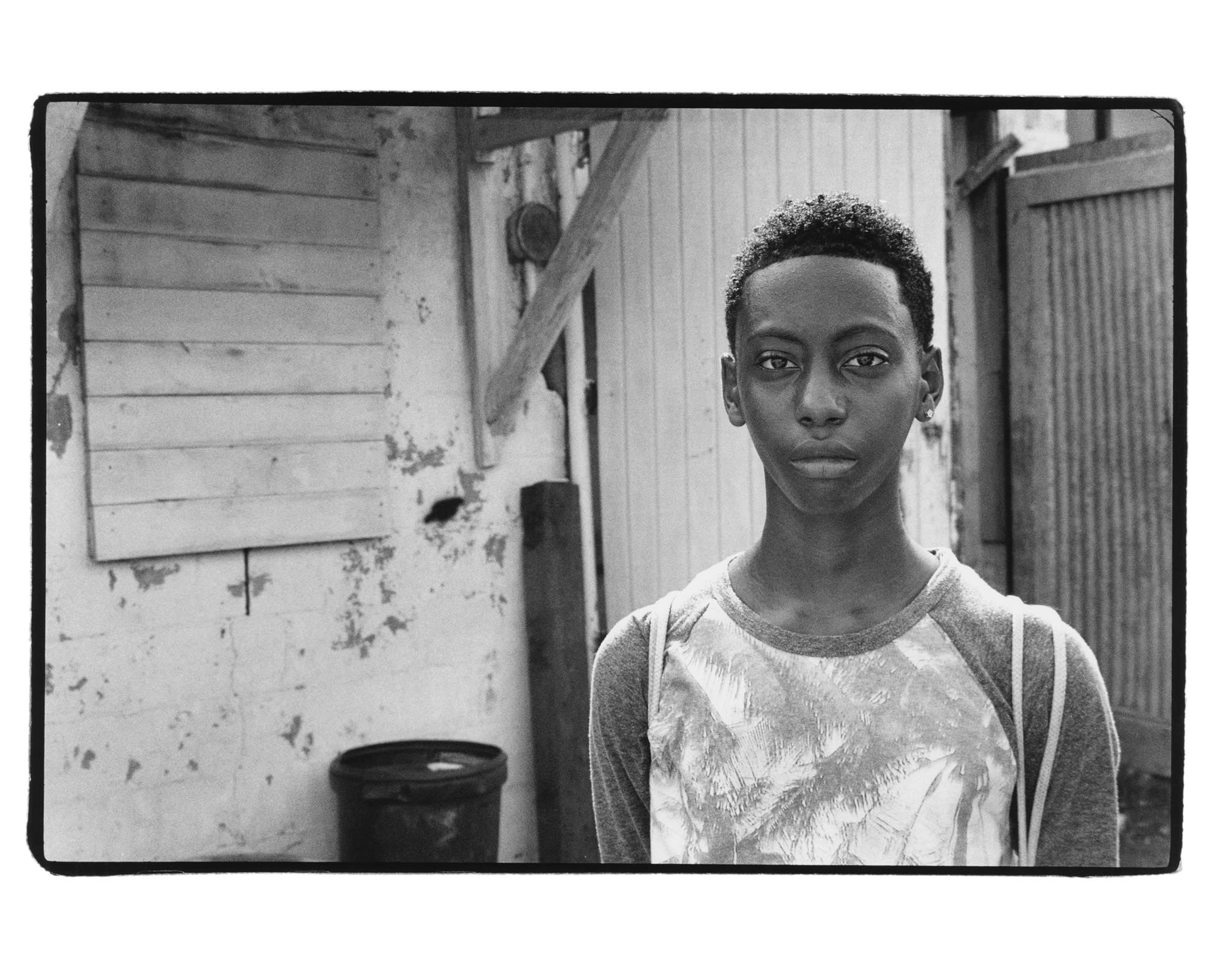

In a portrait of a young man in front of a storefront called “Cross road,” you seem to both be in conversation. When you photograph your subjects, how do you typically connect?

That photograph was taken in Rosedale, a place I have visited countless times. Every trip I’ve made to the Delta over the last ten years, Rosedale is one of those towns that I just keep returning to over and over again. There is something incredibly haunting about it.

The encounters are always random. I just strike up conversations with people. For a long time I photographed where I would try to capture a moment unobserved, and it took me a while to actually engage subject matter. After talking with them, I ask, would you mind if I photograph you? They almost always are incredibly generous and receptive to it. On the cover of the book is a beautiful young man, Quincy, in New Orleans. I talked to him for a long time that day before I finally asked if I could photograph him.

I began to love the immediacy and intimacy of having people look right into the lens, because there’s something that transcends time. Who was it that talked about the delayed rays of a star? You see that as time passes, many years later, that direct, immediacy in the gaze of the missing person, as though you are still there together.

The other thing that I find so fascinating is gesture. I don’t know how to describe it except certain gestures have a tremendous emotional impact on me. If I see a moment where that gesture is present, I will try to capture that. There’s a beautiful quote by Baudelaire when he spoke about the emphatic truth of gesture in the great circumstances of life.

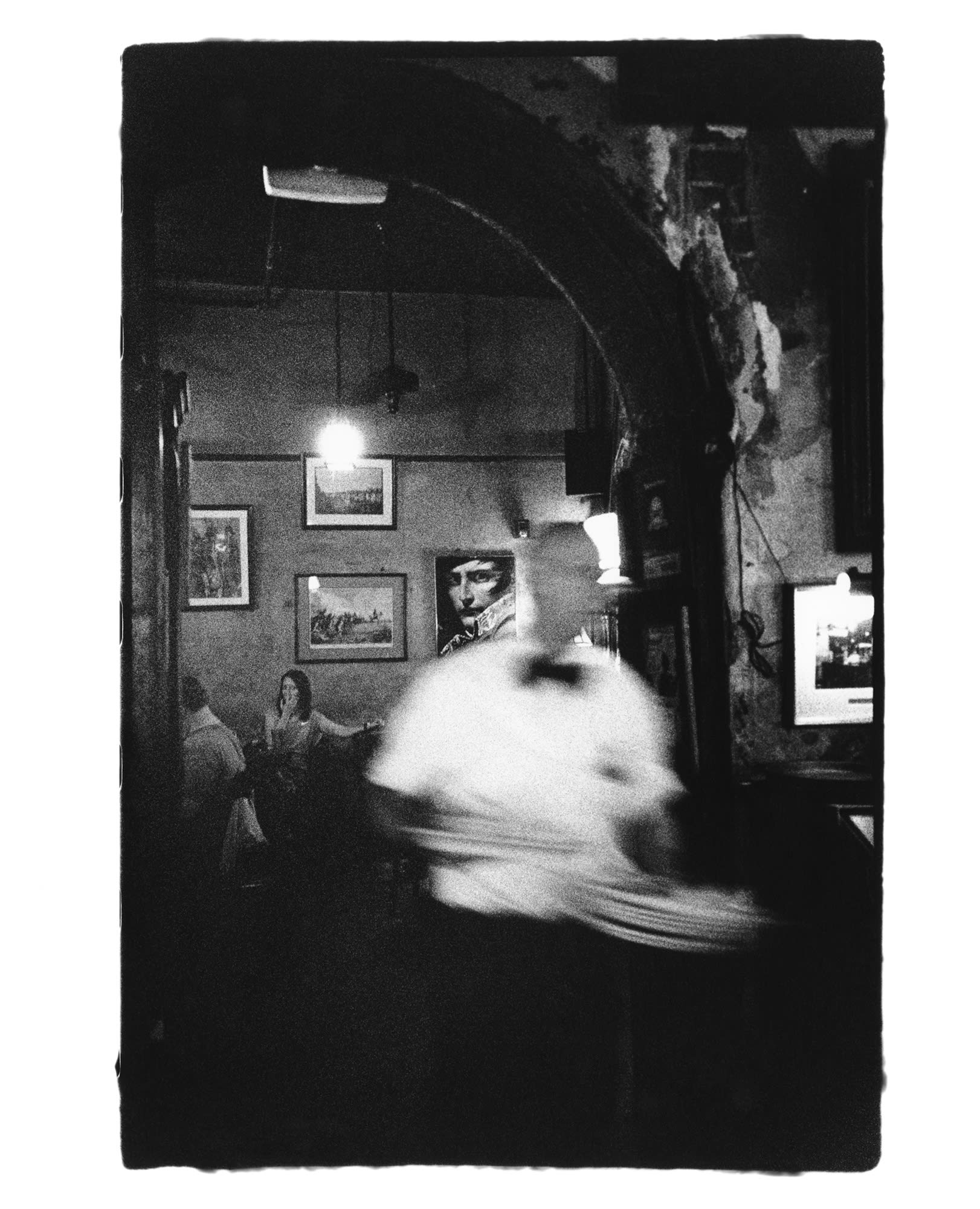

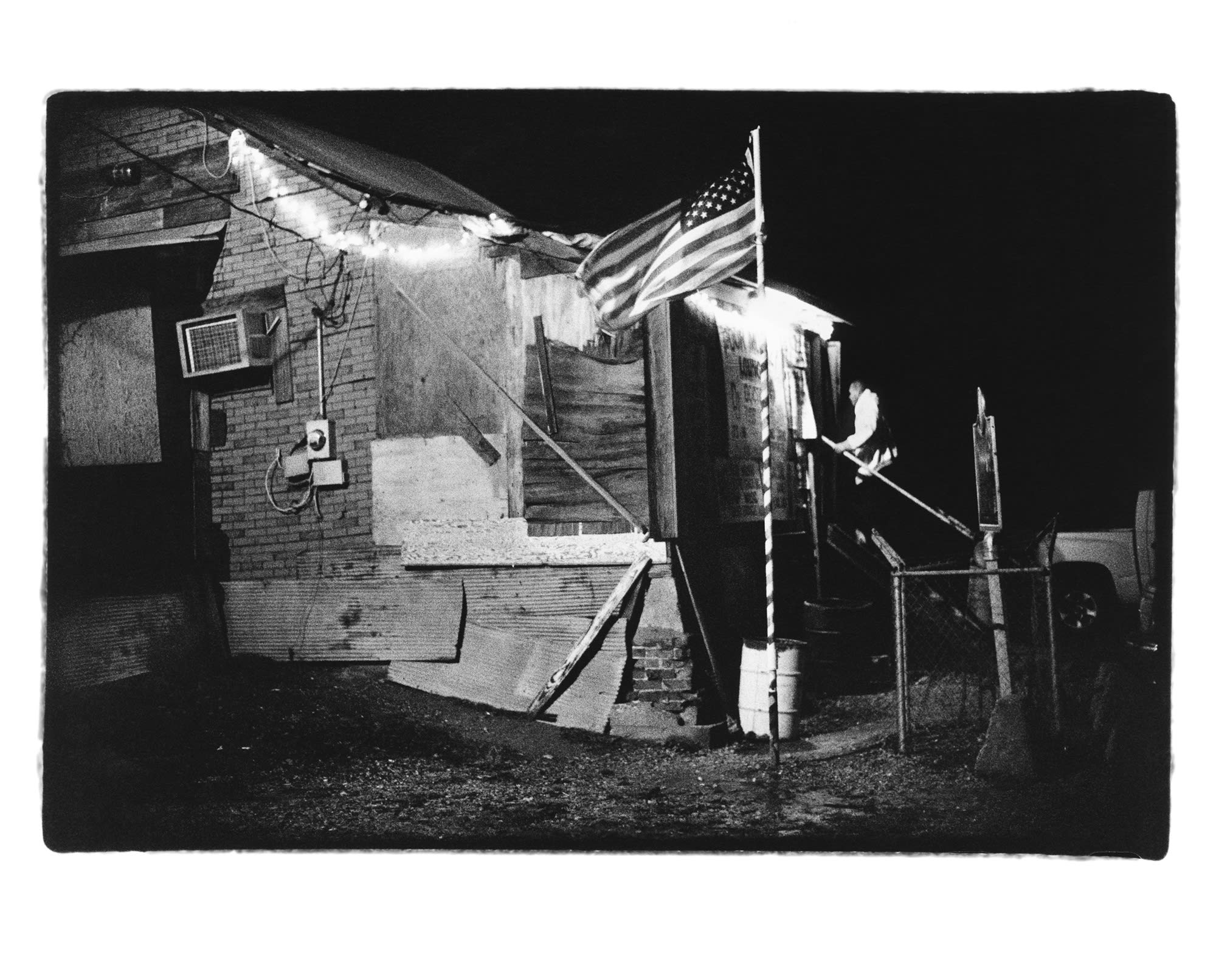

As you travel further south, you photograph in the Mississippi Delta, home of the blues. Several photographs were taken in juke joints — the few that remain today. Can you tell us more about your experiences in the juke joints?

Well it was one of the last juke joints in that stretch of the Delta, its called Po-Monkey’s. It was this legendary place. Again, juke joints were prevalent throughout that part of the country at a certain time, but — of course going back to what we talked about in the very beginning — as this leave-taking took place, a lot of these places disappeared. I believe from what people told me at the time, this happened to be one of the last ones there, and now this too is gone. It was a great community gathering place where people would go to dance, to listen to live music, to play pool, to connect with neighbors and other people in the community. The music was great, the dancing was great. It is too bad to see all these things disappearing.

The thing I remember was an incredible energy and warmth and the way they would welcome you. I’m glad I was able to experience that before the last one disappears.

In the epilogue, you say, “It has been a long drive, wrapped in my story.” Can you tell us more about your story, and how you’ve lived it on Highway 61?

I was born in a small town that Highway 61 ran through. As a child traveling with my family, we would drive it to visit relatives, to go to the county fair, to Fourth of July and memorial day parades, the harvest festival. Of course, as a child, I wasn’t thinking, oh this is Highway 61.

I was born in a small town that Highway 61 ran through. As a child traveling with my family, we would drive it to visit relatives, to go to the county fair, to Fourth of July and memorial day parades, the harvest festival. Of course, as a child, I wasn’t thinking, oh this is Highway 61.

This project came about actually on my first trip to the Delta. I was working in Los Angeles and I had about a week off, and a friend I had just met invited me to come visit so I flew into Memphis and we drove Highway 61 down into the Delta. It was the first time I had ever done that drive, and then a couple of years later I bought a house in New Orleans, where I lived for the next five years.

I suddenly became very aware of the southern part of the highway. The northern part I had known since I was a child and, of course, I still go back there because I have a cabin up in northern Minnesota. For years I had photographed northern Minnesota, all through Minnesota along that route. And now I was photographing that stretch of highway south of Memphis to New Orleans.

Then I thought, well, let me do a road trip, let me do a road book. And so, I started to fill in areas between Memphis and Minnesota. I would drive Highway 61 through Arkansas, Missouri, then Iowa. I never spent a lot of time really in those places. The photography was done driving through, whereas I lived in and spent time in the Delta, in New Orleans, and in Minnesota. It was a different experience. As this friend of mine would tell me, don’t worry about it you are not working for AAA, this is a personal story, you don’t have to worry about documenting everything. It wasn’t meant to be a documentary piece; it is just a chronicle of time spent on this highway.

I can’t tell you how many times I did that drive over the last ten years. I would drive from my house in New Orleans up to my cabin in Minnesota, and I would be going really slowly. I would really just drift up and down that highway. If you were driving straight through it would be a couple of days but if you’re pulling off into a field because you see something, because the light is right, or because somebody catches your eye, or your drive down main street and you see somebody and you end up spending an hour or so talking to them then, you know, it slows you down.

That’s what I meant when I said wrapped in my story. It covers the early part of my life and the last ten years of it.

Interview by Zoe Lemelson.