Back to the Future

by Colin Westerbeck

The only quibble I might have with the Getty’s excellent show, Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography, would be that its title is too literal-minded. A show as exciting as this one is might have had a more adventurous title – say, Back to the Future, or maybe The Framebreakers. On the other hand, the show’s curator, Virginia Heckert, might counter that the material in her exhibition is so full of paradoxes you don’t need to add another layer with a quippy title.

My analogy to the 19th-century Luddites in England, who were hand weavers that rebelled against the industrialization of their craft by smashing the mechanical weaving frames newly invented then, occurred to me because digital technology is causing a comparable upheaval in the history of photography today. But the reaction of the seven photographers in the Getty show to the situation now is more complicated — more witty and contrarian. For what these artists are breaking down and breaking up is not the new invention, but the old ways in which photography has been done since the 19th century.

Consider, for example, the work of John Chiara. Californians will recognize in his landscape photographs a nod to the mammoth-plate camera used by fellow San Franciscan Carleton Watkins to make some of the first photographs of Yosemite in 1861. Chiara’s “Big Camera” is gigundous; it’s a room-sized contraption he trailers to the sites he photographs and in which he can make images as big as 50 x 80 inches. He also goes back to the very earliest experiments in which photographers tried to make direct positives, before the advantage of the negative was discovered. Chiara’s are made on glossy color stock that he processes by sealing it, along with his chemistry, inside a six-foot length of PVC pipe. He sloshes the print around in the chemicals by rolling the pipe back and forth on the floor. The result is a print beguiling in its crudeness, its in-and-out-of focus beauty and irregularly cut edges patched together with Scotch tape.

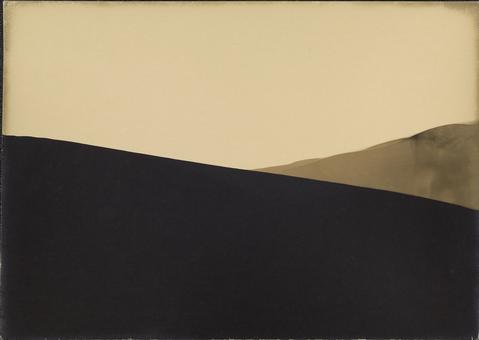

A comparably primitive homage to photography’s past is apparent in all the work in the exhibition. Photographs made now in the vacuum of cyber space and processed in the sterile nether world of the computer have driven industrial giants like Eastman Kodak out of business. It was a civilization, as lost now as that of the ancient Incas, to which Alison Rossiter pays a kind of archeological tribute by finding and processing photographic papers long expired. In the digital darkroom, nothing needs to be left to chance, whereas in her work, everything is.

Her first experiment was with a box of Kodabromide E3 that had a 1946 expiration date. She took a sheet of that paper straight to the darkroom and processed it, as she would all her finds, without having exposed it in a camera. Processed, that first sheet looked, as she put it, “like a rubbing on a gravestone.” Sometimes her surprising results are “found photograms” (i.e.,camera—less images made by putting a physical object on photographic print paper and exposing it to light). Her photograms were created by “light leaks, oxicidation, and physical damage” or were “etched into the emulsion surface by mold.”

Alison Rossiter, American, born 1953, Kilbourn Acme Kruxo, exact expiration date unknown, about 1940s, processed 2013, Gelatin silver print

Source: Artillery Magazine