“This is my place, these are my friends and my people.”

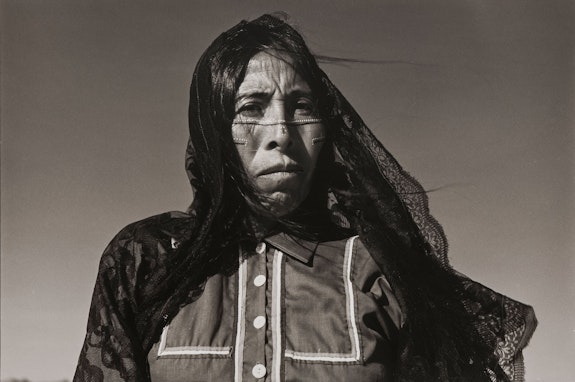

Graciela Iturbide’s photographs are the sorts of images that sear themselves into the mind, the subjects of her portraits becoming familiar figures around which one can imagine entire lives. It’s a generous sort of intimacy she creates, giving viewers depths and details but leaving space to wonder. Since she started shooting in the 1970s, Iturbide’s vision has become visually synonymous with Mexico itself, her photographs reaching through and across the poly-cultural country, asking what one can ever know of another—or of oneself. Following in the footsteps of her teacher, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Iturbide is indisputably one of the world’s most important living photographers. Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico, organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, is on view at Washington D.C.’s National Museum of Women in the Arts through May 25. Iturbide met with Artseen editor Sara Roffino following her D.C. opening to talk about intuition, time, and playing with death.

Sara Roffino (Rail): Let’s start at the beginning, your father was a photographer?

Graciela Iturbide: Yes, he was an amateur photographer and he would take family photographs of me and my siblings. There were 13 of us.

Rail: I can’t imagine that. [Laughter.] You’ve spoken about how you would spend a lot of time with these photographs. Do you recall what was so compelling about them?

Iturbide: My father always kept the photographs in the same place and I would steal them from there. My parents would take the photographs away from me and put them back in the album and punish me, and then I would steal them again. I think I was just always drawn to images. They were photos of my brothers and sisters and my family but I also found some negatives of my father from before he was married and I always loved looking at the light through the negatives. I wanted to make a book with them. Later, my father gave me a Kodak camera and I would take pictures of things like churches and airplanes or on trips, normal things for a child.

Rail: What did you find in the photographs of your father from before he was married?

Iturbide: I actually just rediscovered these and I’m now digitizing them. My father had a tiger, there are photos of him with a tiger in the ruins of Oaxaca. He was a farmer and his parents had a farm, but they lost everything with the land reforms in Mexico. When he was 16 years old he had to go to work to support his parents and by chance he went to work in Oaxaca with the great archeologist Alfonso Caso, so I also have photos of that time in his life and some of him with his friends.

Rail: This seems like an important connection to your own work. It wasn’t just family photographs that you were looking at, the photos were also an entrance into a world that you didn’t know. It’s very different than if the photos had just been of your family. Those photos were a passageway to a different place, a different time.

Iturbide: Exactly, discovering those photographs in my parents’ dresser was really influential. And when I had my little Kodak camera I wanted to be like my father. Also, my parents subscribed to LIFE magazine, which my father loved. I would also look at the photographs and I’ve realized since then that I was looking at photographs by people like Eugene Smith, though I didn’t know who he was then. I would wait for the magazine to arrive each month so I could see the photographs.

Rail: You married young and had three children before going to university to study film. While you were studying you came across a book of photographs by Manuel Álvarez Bravo that was published alongside an exhibition of his that ran in conjunction with the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

Iturbide: Yes, yes, I married young and had my children young and then I started studying film, but I went to meet Álvarez Bravo and shortly after we met, he asked me to be his assistant.

Rail: Right, but then after only two years of working with him, a true master, you decided to separate yourself. Can you talk a little bit about that decision?

Iturbide: Álvarez Bravo didn’t only help me with photography, he helped me in my life. He told me, “Graciela, it is good to separate yourself because you can start again, you can discover so many things, archaeology, books, paintings.” And that opened a whole world to me. I had been educated in a very conservative manner and wanted to study literature, but my parents didn’t think a woman should go to university. Álvarez Bravo opened a world of liberty that I didn’t have. When my husband and I decided to separate, it was okay. The relationship wasn’t bad, but it didn’t function. I was happy after I left my marriage. I had my children and I was studying, taking photographs and sometimes my children would come with me when I traveled into the countryside to shoot.

Rail: How was your lifestyle received by everyone else? It was pretty unconventional for a single woman in Mexico to do what you were doing then.

Iturbide: People thought it was unusual, but I had the support of Álvarez Bravo, who reminded me that there is no normal. He was like a second father to me because my family was horrified that I was divorced and on top of that I was a photographer. I also acted and I had a big role in a film and won a big award for it, but I didn’t let them include my last name because my family would have died.

Rail: Did your family ever accept your life?

Iturbide: Now my brothers and sisters do, but my parents never did. To them I was a communist, a liberal, and a divorced woman. They never understood.

Rail: Was that difficult?

Iturbide: Yes, but for me when I have an idea the most important thing is to see it happen. The other stuff doesn’t matter.

Rail: Álvarez Bravo was reserved in his feedback. He didn’t really share his thoughts about your work. The only thing he said was that you shouldn’t make anything that is political, but taking photographs is always political.

Iturbide: What he said is that I shouldn’t take photographs that are deliberately political because everything is political. All of photography is political and he was right.

Rail: To be an educated woman with resources taking photographs in rural parts of Mexico is certainly political.

Iturbide: I have never deliberately taken photographs with the intention of presenting poverty. I approach my work the same no matter who I am photographing. I have worked with migrants in Tijuana who told me stories about how this was the third time they were trying to enter the United States, but they were always sent back. It broke my heart to see these families there. I’ve also worked in California, in San José, photographing migrant farmers. I think this is the moment to put all of these images into a book so people can see what people are willing to go through to get to the United States if they believe in the American dream.

Rail: So you feel an urgency around this body of work?

Iturbide: The work is already done and I think it is the right moment to show this kind of work. What I love is to go out in the street and take photographs of what I see and allow the project to evolve from that. I like the surprise of discovering what I see and how I feel. But I think now is the moment for that project.

Rail: I see your work as a poetic expression, which I think is a much greater means of expression than something political. The observation and creation of beauty supersedes everything else because it’s not something one can argue with or against. Can you talk about the role of beauty in your work?

Iturbide: I think about it, but I’m not really conscious of it at the same time. When I see something and feel it, I take the photograph. But I think a lot about poetry and I love reading Sufi poets and San Juan de la Cruz. Poetry is very important to me and if there is something poetic in my work that is great, but the truth is that I don’t know, that is something other people will have to say. Álvarez Bravo told me that I had to listen to music, I had to read a lot, look at paintings because all of these different influences will be reflected in my work.

Rail: What are you reading now?

Iturbide: I’m reading a lot of history books, about Mexico before the Spanish conquest and during the colonial era. I just finished the book of Nezahualcóyotl, who was a king poet before the Aztec Empire was established and who wrote marvelous poetry. According to what I have read about him, there were also female poets in his house. He thought that perhaps there was just one god, not many, which was the Aztec belief. He had his own expansive ideas on life and religion, which are fascinating to read, but above all is his poetry. The book is called Flor y Canto.

Rail: You’ve spoken about feeling like an intruder when you first began visiting the villages where you would photograph, but with time that feeling opened up into something else. Can you talk a little bit about that shift? Was it a specific moment or something that happened?

Iturbide: Things started to change with time. I went to live in Juchitán for a month. I stayed in homes there and spent days in the market with the women. It became very natural and when they came to the city they would visit me at my home. Anthropologists talk about “the other”—and I understand that when Dutch or French photographers came to Mexico during the colonial era to photograph the ruins and take images of an exotic place it was as “the other.” But I am Mexican and I feel equal to the women of Juchitán. I slept in their homes and they cared for me and I cared for them. It was the same with the Seri women, who I also worked with a lot. I’ve spoken a lot about this with the renowned historian Alfredo López Austin, who is writing a book about the ideas of “the other” in Mexico. It was a concept that emerged when Europeans were coming to take photographs in Mexico, but I am Mexican. This is my place, these are my friends and my people.

Rail: Did you know anything about life in the indigenous villages before you began working there?

Iturbide: When Francisco Toledo, the great painter who unfortunately passed away last year, invited me to Juchitán, I had read some of Miguel Covarrubias’s writings about Juchitán and some of the magazines that Toledo had made in Juchitán and Oaxaca. Toledo was from Juchitán and the people there loved him, so even though we arrived during Semana Santa (Holy Week), we were welcomed immediately. The women brought me to their homes and helped me and we were quickly friends and they are my dearest friends now. I lived with them and shared everything with them and it was the same with the Seris. I arrived just with my camera and told them I was a photographer and that I was going to take photos and if they didn’t want their photo taken to just let me know and I wouldn’t take their photo. I never use flash and I work at a close range, so I am always aware of the space I am in and I respect it. I felt completely at home with them, more so than anywhere else I have worked and I was incredibly happy living with them.

Rail: Do you think of your work as a collaboration?

Iturbide: It is a collaboration. The people I am photographing know what I am doing and sometimes they ask me to shoot them in a specific way and I’ll do that, but it’s not usually that formal. More often, I’ll be at a party or something and people will know I’m taking photographs and if they don’t want me to photograph them I don’t.

Rail: The world has changed so much since then. How has the way you work changed from when you started out?

Iturbide: I’ve worked all over. When I was in Madagascar with Doctors Without Borders, the people all loved having their photos taken. It was nonstop, “madam, photo, photo!” I didn’t know what to do so I would have to take photos of hundreds of people. In India, it was the same, so I asked my assistant to shoot with her video camera because I couldn’t take all the photos that people wanted me to take. Things have changed for sure, when I first started working more people didn’t want their photos taken because they thought it would rob their soul, but now it is different and now I travel more. What I love the most is to photograph in Mexico, but it is difficult to go to these communities now because of drug trafficking. The women in Juchitán, for example, wear their gold around their neck, like a little bank, but now they can’t do that because everything gets stolen. It’s the same with a camera. But when I can go, I do. I just finished shooting a series of photographs at the refuge house of Padre Alejandro Solalinde in Oaxaca, which helps migrants and other people in need. I also started taking photographs of objects and landscapes in ways I had never done before. It’s partly about always looking at how I can photograph things in new ways, to discover new symbolism and meaning.

Rail: I’m curious about your thoughts on time. It’s not possible to separate the art of photography from the concept of time. From Henri Cartier-Bresson’s idea of the decisive moment to Roland Barthes’s understanding of the image as inherently also a marker of a kind of death. With Álvarez Bravo, there was a refrain about having time, or the idea of Mexican time. How do you think about time within your work?

Iturbide: Yes, Álvarez Bravo would say to me, “There is time, Graciela,” don’t rush to shoot, do it calmly. I would go out with my camera and take pictures of everything. But Álvarez Bravo would only take one photograph. I don’t know how he did it. This is incredibly difficult. I take two photos in case one is blurry. I react to the moment and I shoot when something surprises me, whether it’s in the villages or in a foreign country. I think also about a lot of the photographs I have wanted to take, but didn’t—either because I couldn’t photograph a particular person or because I missed the moment. These all remain in my heart. Ideas for photographs that stay with me, but that can’t be reconstructed because the time has passed. I remember one trip Álvarez Bravo took where he only brought one roll of 35 mm film. That was everything he had for the trip. If I take a trip I have at least 15, 20 rolls of film.

Rail: How do you see the role of intellect versus the role of intuition in your practice?

Iturbide: My work is completely intuitive. Of course, everything I look at and read influences me in some way; for example, I love Piero della Francesca, so maybe if I see something that reminds me of his work I recognize that in some way, but it is completely unconscious.

Rail: Is intuition something one can learn or cultivate?

Iturbide: I think you can cultivate it, I think we all have intuition. For some people it’s more developed than others, but intuition exists within everyone. Sometimes we forget about it and we don’t cultivate it, or maybe there is some that is blocking. I don’t know, I think.

Rail: You only shoot analog and you take many photographs. How do you know which one is the right one when you are developing them?

Iturbide: Cartier-Bresson spoke about the decisive moment. I think there are two decisive moments. I still work with silver and gelatin and I love this ritual. I don’t ever shoot digitally, not because I don’t like how it looks, but because when I begin to develop my photos and I have direct contact with them is when I realize that many of the photos that I thought would be good aren’t good. And then I see which ones are good and sometimes I don’t even remember taking them. So, for me, there are two moments, the moment I take the photograph and the moment I choose the photograph.

Rail: Right, like with Mujer Ángel [Angel Woman] (1979), you don’t remember taking that one.

Iturbide: Exactly, I remember when the woman was walking down and I remember when we all had arrived below, but I don’t remember taking the photograph. Obviously I took it, but for a long time I wondered if the anthropologist I was with had actually taken it. But it’s not possible.

Rail: I imagined that you had been waiting for this moment, for her to pass, because the photo is so perfect. I wondered how many times you waited in this place for her to pass and how many times she had to pass to get this image.

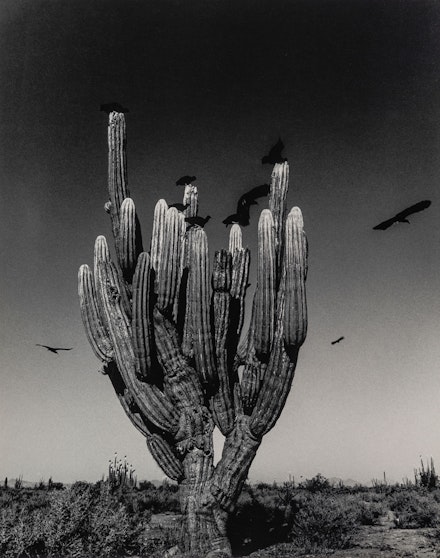

Iturbide: It is a miracle. I say that this photo was a gift from the desert.

Rail: My next question is sort of about poetry, but also surrealism. The idea of surrealism is complicated for Mexicans because it’s something that North Americans and Europeans have applied to their understanding of Mexican culture and art, but it’s not necessarily how Mexicans would describe themselves. In Mexico, there isn’t the polemic between tangible and intangible that exists in European cultures. Your work moves within this space of what exists physically and what exists but not necessarily in physical form.

Iturbide: I haven’t seen this in my work, but thank you. When I was in France and people would talk about a Latin American viewpoint, I would have to stop them and say no, how is there possibly a Latin American viewpoint? What does Chalma, for example, a little tiny village where people make a pilgrimage to celebrate the Archangel San Miguel, have to do with Argentina or Paraguay or Colombia. And, moreover, what does that have to do with photography? Every photographer has their own personality and every photographer sees according to who they are, so when people would tell me that my photography is Surrealist, I would explain that the Surrealism of André Breton was a moment and it gave us many things, but it was a moment. In Latin America, we do not like when the French or other foreigners give us these labels like magical realism—no! People talk about this boom of magical realism as a way of commercializing something, but it’s completely patronizing and paternalistic.

Rail: It’s a lack of seeing the complexity of existence. You’ve taken many photographs of rituals: the Mixteca goat slaughter, celebrations of life and death throughout the world, courtship practices in Juchitán, among many others. What are some of the rituals you practice in your own life and work?

Iturbide: I think everyone has rituals, starting with how we wake up in the morning, listening to music, there are many daily rituals. In photography, when I arrive to develop my roles of film I put all the contact sheets out in front of me and often I cut out the images and put them on little cards—this is my ritual. It’s the second moment that I spoke about earlier, the second decisive moment of deciding whether the photograph is one to print or to keep in the box.

Rail: For many years you focused on photographing death. What did you observe or learn about death through all the images of it that you took?

Iturbide: From when we are children, Mexicans are accustomed to living alongside death. We play with death, but we also are afraid of it and I think this is why we play with it. This is why on the Day of the Dead we give each other sugar skulls with our names on them and eat them. We also dress up like death as a way to play with it—I think also because we are afraid of it. In Nezahualcóyotl’s poems he says, we all pass through here, we are all coming here to die. This was an important concept in pre-Hispanic times, but with the arrival of the Europeans, it shifted. Now we play with death, but we are also afraid of it.

Rail: Do you think you are less afraid because you have spent so much time thinking about it and working with it?

Iturbide: I am used to playing with death, but obviously I am also afraid of its arrival. [Laughter.]

Rail: Of course. Working as a photographer now is so different than when you started. Do you think it’s still possible for a person who is just starting out to tell stories the way you have?

Iturbide: Yes, of course! We look at so many images now, in advertising, on television. We are full of images. But when your world is images, this doesn’t matter. You still make and develop your work because it is the work of your heart. So yes, if someone wants to tell stories with images and they have the passion and the discipline, then of course they can still do it.