MEXICO CITY— What are the images that define contemporary Mexico? In the foreign eye, they are pictures of migrant caravans, escaped drug traffickers, beaches conjured by the American imagination.

Mujer Ángel, Desierto de Sonora (Angel Woman, Sonora Desert), México

Which is why 2019 is the appropriate year for the world to discover Graciela Iturbide, who now has extensive exhibitions in Boston and Mexico City. For a half-century, Iturbide has traveled across her own country with a camera loaded with black-and-white film. She has taken pictures that are often described as dreamlike, surreal or painterly, but those words fall short.

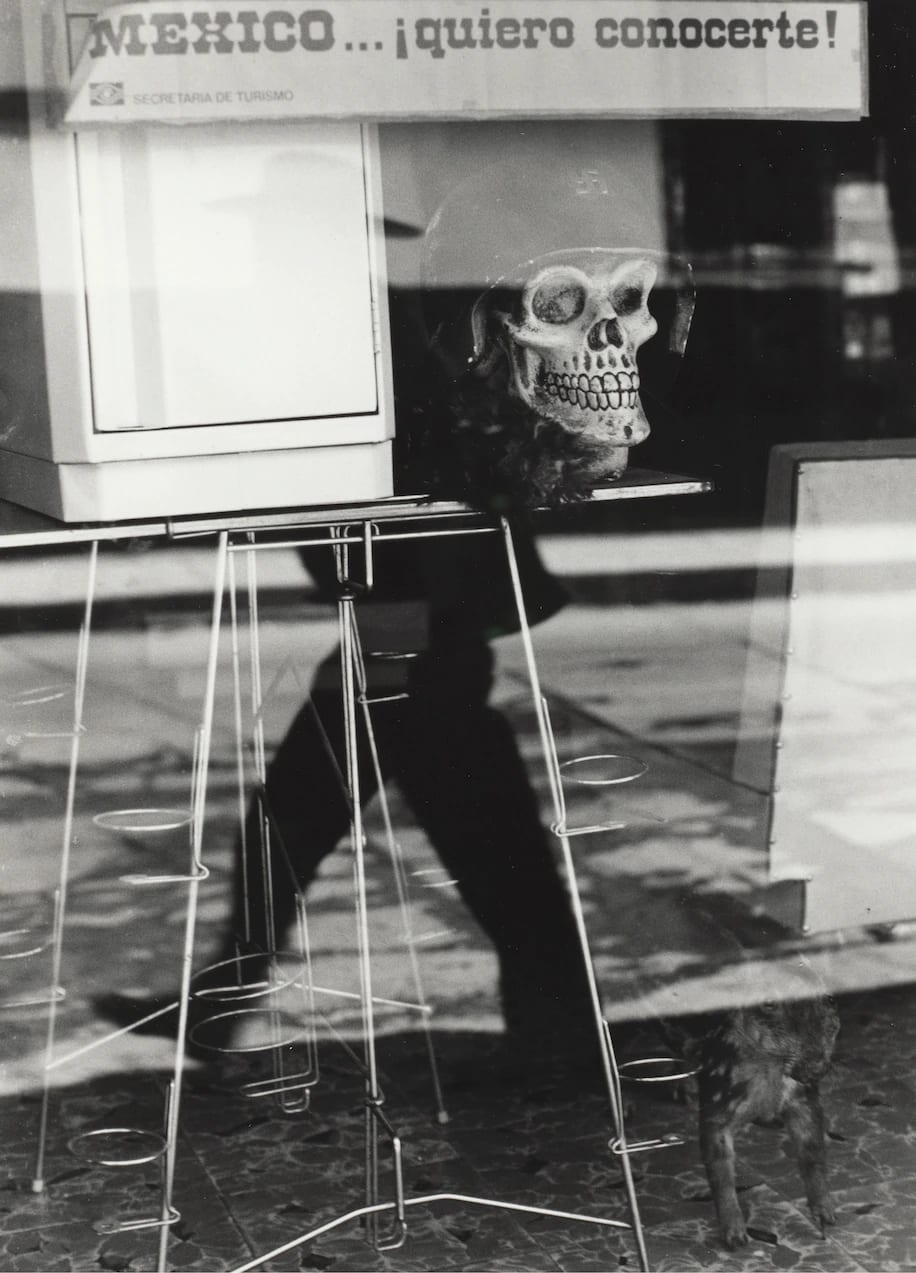

They are the visual opposite of the Mexico we have come to expect, simple and violent, a projection of our own fears. Iturbide’s work is instead an exploration of a nation’s subconscious, not strange or beautiful for the sake of aesthetics, but because of what the work reveals.

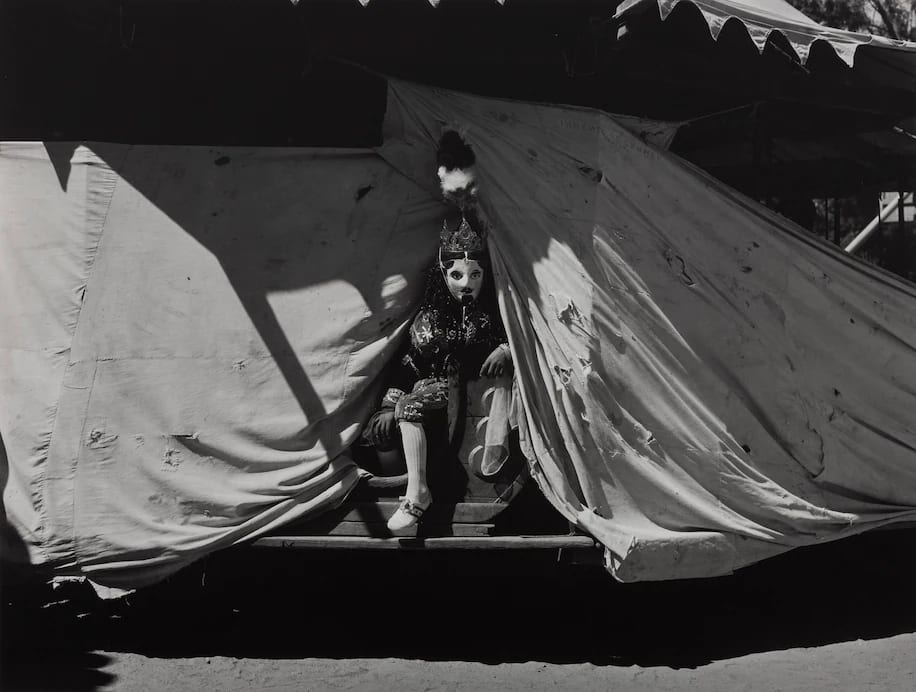

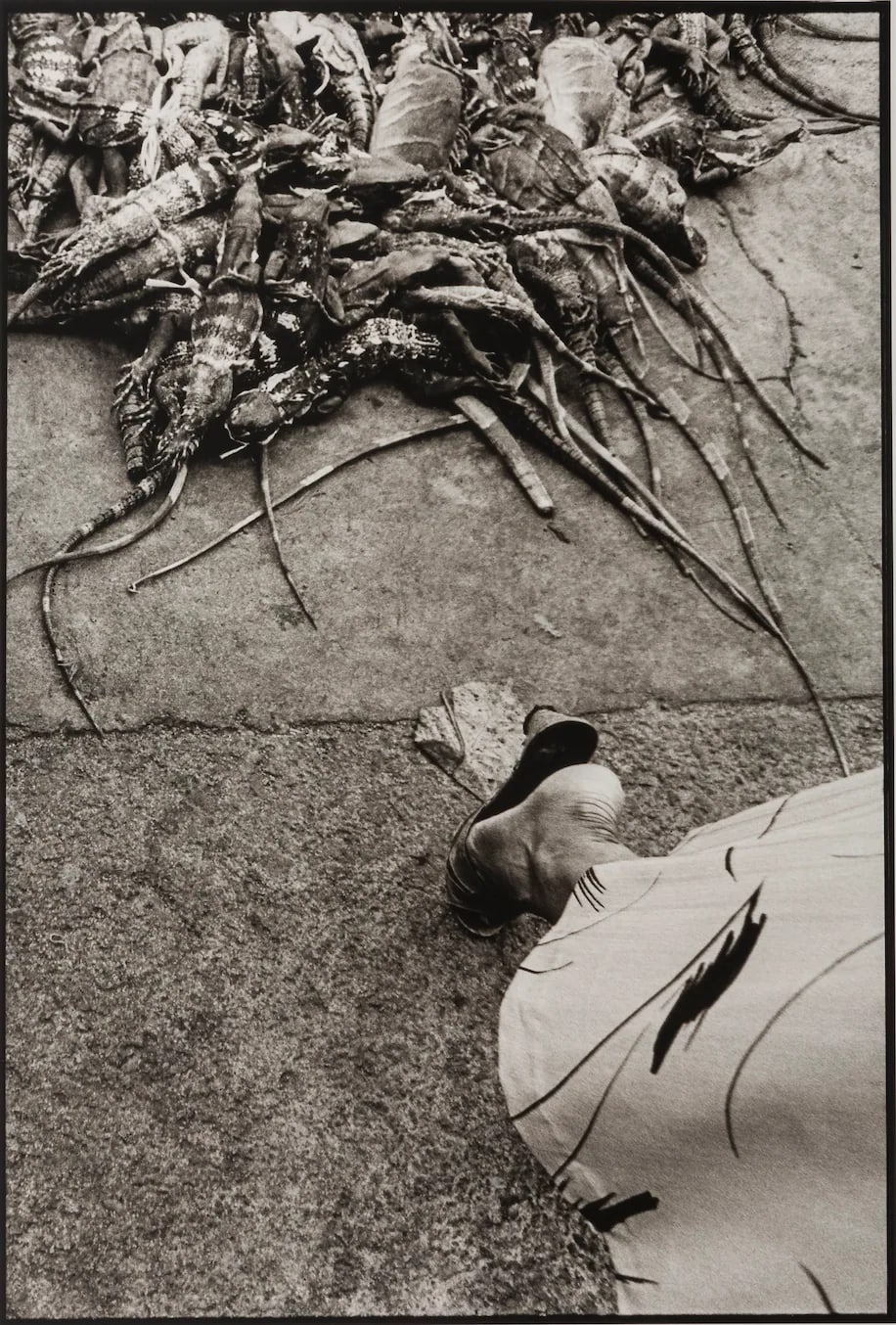

A flock of birds, like a dark cloud, soars over a power line in rural Guanajuato. A woman in a white dress walks on a mountain bluff, seeming to hover above the earth like a ghost. There are portraits of men in carnival masks, a pile of dead iguanas, a pickup truck plastered with angel wings.

What do we see when we look at those images, which are not quintessentially Mexican in any sense? Even the pictures themselves are incomplete: torsos without heads, masks without faces, birds blurred and truncated by the frame. We see pieces of a whole, fragments that take on more meaning with each picture, a nation reimagined image by image.

Iturbide’s new exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts is called “Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico,” suggesting that what we ought to see in her pictures is a coherent way of interpreting a misunderstood nation. But Iturbide never set out to document her own country. “I only photograph that which surprises me,” she said in an interview in her home last month. “And from there, I develop my obsessions.”

On her wall was one of her few color prints: a picture of Frida Kahlo’s prosthetic leg, bent at the knee, in the artist’s bathtub. Iturbide had been invited to photograph Kahlo’s house in 2005. What she documented was an antidote to the brand Kahlo has become in death, another Mexican fiction. Kahlo’s prosthetics are now displayed as fashion accessories at museums in New York and London. Instead, we see the leg splayed, the tub dirty, a tiny window into a life lived, raw and complicated and irreducible.

Volantín (merry-go-round), San Martin Tilcajete, Oaxaca, Mexico

Torito (little bull), Coyoacan, Ciudad de México

Pajaros en el poste (birds on the post), carretera a Guanajuato, Mexico

Mexico, Quiero Conocerte!, Chiapas, Mexico

Chalma

Iguanas, Juchitan, Mexico

Jardin Botanico, Oaxaca, Mexico

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.