The Japanese photographer’s latest work, made during her early years of motherhood, gently reminds us to treasure the everyday

When Rinko Kawauchi arrived on the international art scene in 2001 with the simultaneous publication of her first three photobooks, Utatane, Hanabi and Hanako, her work was lauded for its simple yet sublime portrayal of the everyday. Just under two decades have passed, and the Japanese image-maker has now published over 20 photobooks, many of which ponder the simplicities of daily life. Cui Cui (2005), for example, is a collection of over 13 years of memories with the artist’s family, and Aila (2005) captures transitory moments in the lives of animals, landscapes and objects while ruminating on the relationship with life and death. Then, in 2013, a strange dream forced Kawauchi to consider a very different and more turbulent set of motifs. It led to a stylistic departure and a thematic shift towards ideas of existence, mortality and time, resulting in the capture of the roaring, celestial landscape seen in Ametsuchi, published by Aperture in the same year. The title is taken from two Japanese characters that together mean ‘heaven and earth’.

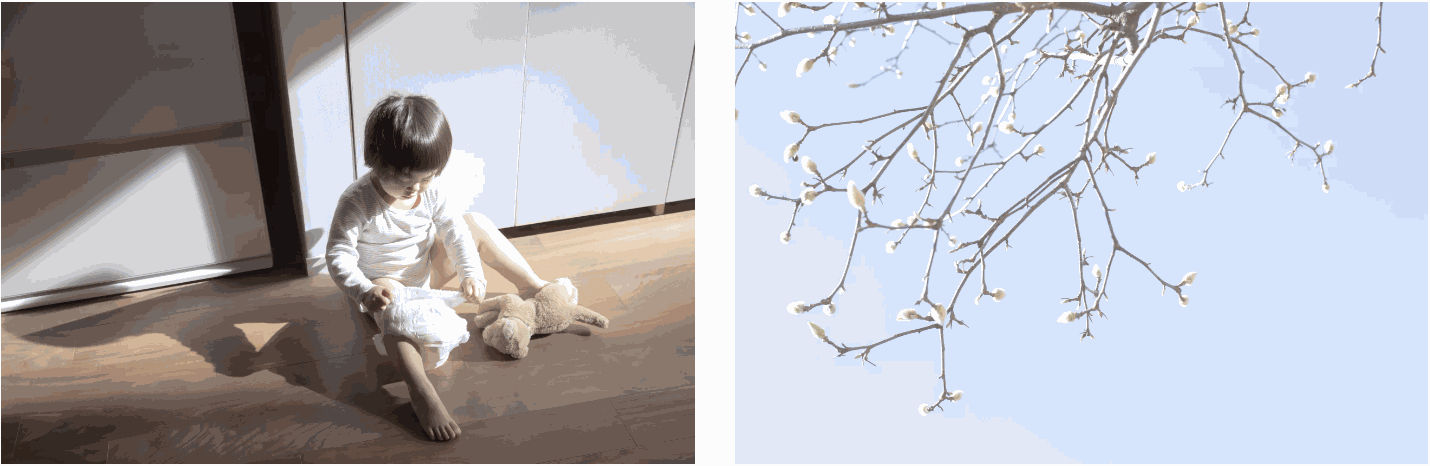

Kawauchi continued to explore these great themes in Halo, a series that she created in 2017, the year after a new arrival transformed her future forever. “Having a child changed my outlook on life,” says Kawauchi, who gave birth to her daughter four years ago. “Before, I struggled to perceive existence itself in a positive way. When you have a child, you have to stay healthy for them to keep living… I have to stay alive now, even if I don’t want to.” Kawauchi’s latest photobook, As it is, published by Chose Commune, in collaboration with Japanese publisher Torch Press, presents candid and gentle snapshots from her daughter’s formative years, and the verdant landscape that surrounds their home in Chiba prefecture. In tune with her earlier works, the artist finds beauty in simple scenes – a bright blue sky, a blade of grass, or a tiny frog clutching at a window pane amongst fresh globules of rain. Punctuated by signs of the shifting seasons and small inserts of written poetry interspersed throughout the book, the narrative blurs and wanes between fleeting encounters and moments of quiet intensity: a bowl of rice, her daughter’s first steps, the passing of an elderly relative.

Born in 1972 in Shiga, a southern prefecture east of Kyoto, Kawauchi has fond memories of her own upbringing. “When I look at my daughter, I think of my own childhood, and I remember things that I had forgotten,” she says. The photographer’s earliest memories were gathered amongst plentiful parks, mountain ranges and Japan’s largest freshwater lake, until her family relocated to the outskirts of Osaka, a port city south of Kyoto, when she was four.

Kawauchi picked up photography when she returned to Shiga, aged 19, while studying graphic design at Seian University of Art and Design. She knew she wanted to become a photographer, but needed to expand her technical skills first. So instead of going back to school, she spent the following four years working for commercial photography studios in Osaka and Tokyo. “It was a way to earn money while learning,” she says, explaining that it gave her time to build her personal portfolio, while applying for grants and competitions. Her breakthrough moment arrived in 1997, when she was awarded a solo show at the Guardian Garden gallery in Tokyo’s Ginza district, which led to the 2001 triple-publication of her first photobooks, and winning the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award the following year. International recognition followed swiftly; in 2004, Kawauchi was invited to exhibit at Les Rencontres d’Arles, and in 2009, she won the ICP Infinity Award, followed by the Royal Photographic Society’s Honorary Fellowship in 2012.

“Part of why I make photographs is to confirm my existence. This liminal space is what feels closest to how I experience reality”

Those who are familiar with the photographer’s work may sense a thematic retreat in her latest publication. But, for the artist, every photobook feels like a “step forward from the last”, she says. Reflecting upon her oeuvre, many of her works revisit the same motifs. Nature, the cycle of life, and family, for example, but most prominently, dreams. With Ametsuchi, it was a dream that led her to Aso, a volcanic region famous for its ancient farming rituals, and Utatane, the title of her first publication, refers to the state of being half-asleep. “I dream a lot,” says Kawauchi, but, rather than mimicking a dreamlike state in her images, it is the space between reality and fantasy that she seeks. “Part of why I make photographs is to confirm my existence,” she explains. “That liminal space is what feels closest to how I experience reality.”

In Kawauchi’s practice, reality and the spiritual world consistently interact – be it conjuring a magical realism out of the mundane, or shooting otherworldly landscapes. Shinto, Japan’s indigenous and most common faith, is based on belief in ‘kami’, loosely translated as ‘god’, but more accurately, sacred spirits that take the form of important objects and concepts, such as elements of the landscape. Kawauchi believes in the existence of a greater force within nature, which she experiences “in the sunset I see every day from my home, or when I encounter a kind of light that can only be seen in that moment”, and she seeks to capture this through her photography as well.

Contemplating our relationship with nature and the cycle of life feels poignant, as Kawauchi and I speak from a safe distance in her publisher’s office in Tokyo, both of us wearing facemasks, occasionally peeling them aside to sip on iced coffee. It is mid-September in Japan, and life is somewhat returning to normal. But, elsewhere in the world, a second Covid-19 lockdown feels imminent. There is a sentiment that the world has been reminded of a force far greater than humanity, and revisiting Kawauchi’s work is a reminder that nature is not only a source of beauty, but a place of refuge. In its simplest form, her work teaches us to recognise its subtle gesturing, be it a cloudy sunset, snowfall at night, or the shifting seasons, spent with people we love.