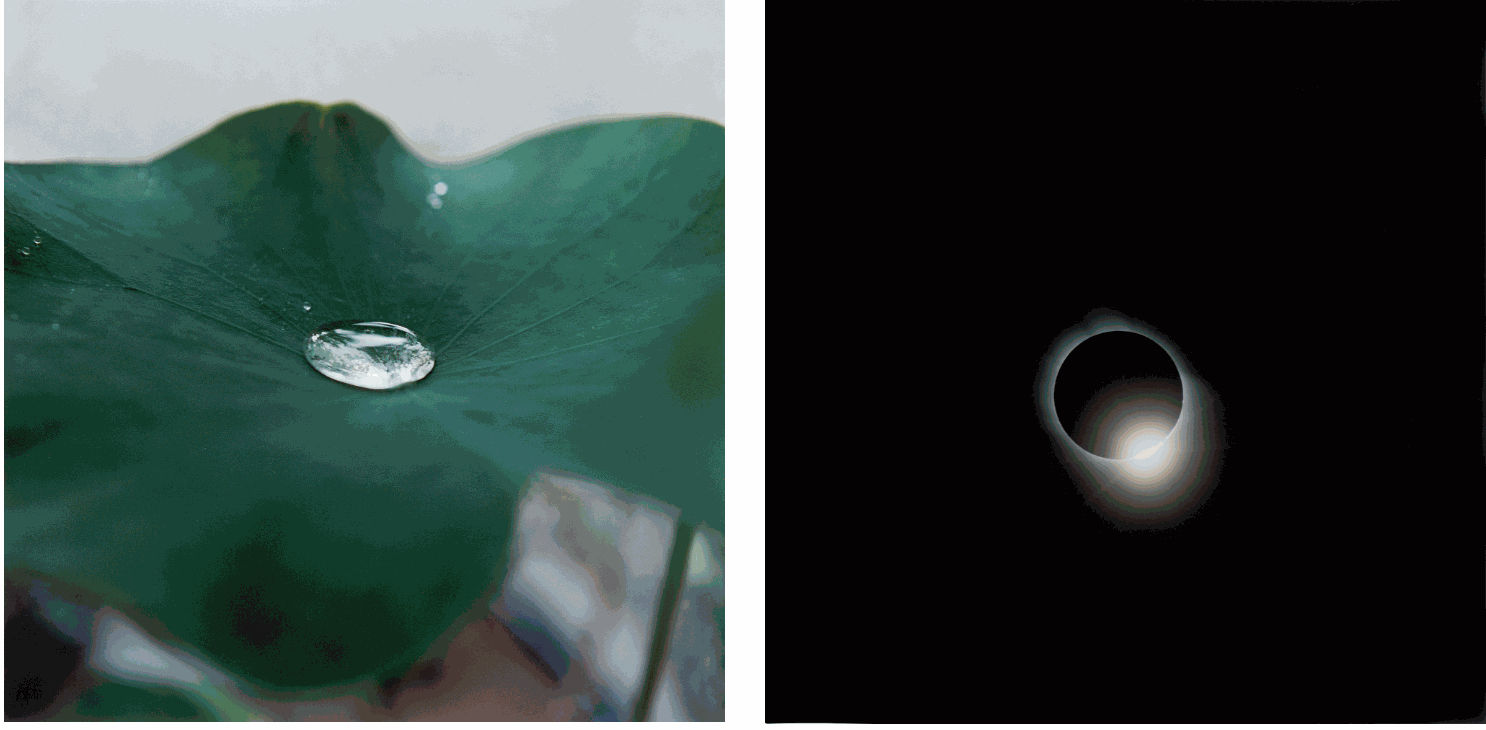

In her images of keenly observed gestures and details, Kawauchi reveals the mysterious and beautiful realm at the edge of the everyday world.

The current ecological crisis urges us to formulate new ways of thinking about the real world in which we live. The increasing prevalence of natural catastrophes, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, and wildfires, stirs the fundamental conditions upon which the existence of humans depends. In this moment, we are forced to admit that we cannot be free of the inertia of material reality. As Amitav Ghosh puts it in his Great Derangement, “The stirrings of the earth have forced us to recognize that we have never been free of nonhuman constraint.” In a sense, we realize that humans are not free agents but instead are caught within a nonhuman realm—and far from mastering it, we are constrained by it. We feel that we are thrown into vast depths without surfaces or boundaries. We are caught within a truly wild dominion of openness.

Yet we are also, in another way, oblivious to it, because this realm is suppressed beneath the superficial representation of the smoothly functioning everydayness made manageable by the logic of late capital- ism. Contemporary art has often been complicit in this obliviousness. According to Ghosh, “Human consciousness, agency, and identity came to be placed at the center of every kind of aesthetic enterprise.” For that reason, most dominant artistic practices are so bounded by the anthropocentric view that they become impervious to the shock of the ongoing ecological crisis. Even though a natural disaster such as an earthquake urges us to examine the exterior reality beyond human consciousness, artists often appear oblivious to the harsh realness of the world.

As is well known, in March 2011, Japan was horrendously damaged by the tripartite catastrophe of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident known colloquially as 3/11. In the face of this unprecedented event, which inflicted severe harm on those living in the villages and towns in the Tohoku area, Kawauchi responded as a photographer. After that incident, she walked around the area, took photos, and published the results as Light and Shadow (2014). Her response was not directed at the tragedy she witnessed; rather, it was oblique. Her photographs force us to encounter the inert materiality of the world that is emancipated from the glittering surface of the spectacular world.

One of the themes of that book is silence. Depicted in its pages is a pair of pigeons, one black, the other white. The pigeons, who had been uprooted during the tsunami, were in search of safe haven. She writes the following:

Looking at these pigeons, I thought of them as symbols of so many things, especially the dualism of our world. White and black, good and evil, light and shadow, man and woman, be- ginning and end. Throughout existence there have been, and will be, innumerable occurrences of delight and dread.

Because of the devastation, many things, including pigeons, were certainly expulsed from a previously stable habitat. They were uprooted. Yet, on the other hand, an earthquake reveals to us a hidden reality that usually remains submerged beneath the consistent and coherent yet illusory framework of the present world. Such an event urges us to encounter the otherness of the ambiguous realm with its “innumerable occurrences of delight and dread.” A dark and shadowy sphere may have existed prior to the stable consolidation of the present world—an undifferentiated state of heaven (ame) and earth (tsuchi).

The reason I am fascinated by Kawauchi’s photos is that they enable us to be susceptible to the doubleness of reality. The world that we inhabit is not only the self-contained human world. Simultaneously, it is open to the mysterious realm that operates at the edge of the mundanity of the human lifeworld. Her act of photographing is less a way of referring to the appearance of everyday reality than it is a revealing of the luminous open space within which sensuous elements are free-floating. That is to say, in her practice, a sequence of photographs does not fix the appearance of everyday events, but rather evokes the realness of ambiguous ether that existed prior to the fixation of the predominant worldly setting.

Illuminance was published the same year that the catastrophic earthquake happened. I feel it is something like a prophecy of the unprecedented event that totally changed what Raymond Williams calls the “structure of feeling” for all of Japan. Ahead of this shocking incident that revealed to us the fragility of the human world, Kawauchi’s photographs attuned us to its intrinsic frailty.

In an interview, she related the following:

I need many elements to come together in a series to create a mood, not just portraits—including seemingly unrelated subjects, such as landscapes and tiny details, as well as different moods and atmosphere, expressing my own feelings about time passing, the fragility of life. They are metaphorical images, really, [about] how fragile our world is.

The idea that our world is fragile does not mean that it is doomed to extinction. Rather, according to Kawauchi, fragility concerns her feelings about time passing. Perhaps this means that things in our world are perishable. In a way, Kawauchi’s sense of fragility is in accord with Timothy Morton’s statement, “In order to exist, objects must be fragile.” Both of them seem to intuit that everything is ephemeral to the point that it cannot be fixated—in other words, fragile things in this world are not individually fixed objects but rather lose their separateness.

What is remarkable about Kawauchi’s photographs is the way they evoke the sense of mysterious openness at the edge of the everyday human world. One of the images included in this volume depicts an upward-leading stair that middle- and high-school students are ascending, for instance, is photographed in such a way as to show us the vastness of the exterior world that surrounds and penetrates our ordinary living. Illuminance, the title of this photobook, indicates the realness of what is beyond and above our own reach. The fact that something can be illuminated means that some other thing remains in shadow.

What Kawauchi reveals to us is the sensuous realm within which the boundary between things becomes blurred. It is filled with light. David Chandler holds that “Illuminance builds into a sustained meditation on light’s miraculous qualities and revelatory power.” Certainly, light is endowed with an active power that brings something invisible into the visible. Yet, we should not confuse Kawauchi’s revelatory use of the power of light with the violence of light. According to Jacques Derrida, the neutrality of lightning, pure transparency, is often synonymous with the violent oppression that makes everything the same. That is to say, within the neutrally lighted space, “to see and to know, to have and to will, unfold only within the oppressive and luminous identity of the same.”

Kawauchi’s light is quite contrary to this violence criticized by Derrida. Rather, she shows us that there is a different kind of light. In Kawauchi’s Illuminance, Chandler argues, “light obscures as much as it reveals: it reflects, penetrates, dematerializes, and renders things invisible.”

How do we think of light that obscures and dematerializes things? Perhaps it evokes a spacious realm within which things become indistinct, deep beneath the surface of our common perceptual framework. I argue that Kawauchi’s act of photographing captures what Alphonso Lingis calls “luminous openness.” According to him, the light that fills visual space is not transparent; rather, “its radiance fills and thickens the space such that the surfaces of gleaming or shadowy things at a distance are dissolved in it.” Objects within luminous openness are not identifiable nor fixed.

They remain ambiguous. The radiance is sometimes so pervasive that we can demarcate nothing in it. Prior to the construction of the perceptible framework of human consciousness, there was such a luminous openness. Thus, the reason why Kawauchi’s light is different from the violence of lighting is that it allows for the playfulness of sensuous elements—it amplifies the openness and weightlessness of the spacious realm, so as to enable multiple elements to resonate with each other.

Kawauchi’s practice reminds us of how the conditions in which we exist are fragile and vulnerable. The natural world underneath the human-made world cannot be completely mastered by the act of human will. On the contrary, it stirs and disrupts the human world. In a sense, the world is independent of us, indifferent to our concern. As Dipesh Chakrabarty reminds us, we encounter “the radical otherness of the planet.” This otherness, or the earth’s uncanny aspect, is revealed to be beneath the human lifeworld. It belongs to another kind of reality, the underworld of things, which remains on the edge of human life.

Illuminance shows us that the world we truly inhabit is withheld from our consciousness, or rather, it reveals that things in the world’s luminous openness are endowed with an aspect that is not empirically observed: the shadowy aspect. To be in shadow is not so much to be in mere darkness, but rather to be vaguely cast in light. Within a realm of illuminance, one that existed prior to the neutral light of violence, the essences of things are manifested—yet, quite mysteriously, the world of things is independent of us. Kawauchi’s work, however, allows us to witness this shadowy realm on the edge of the everyday. Like weeds growing through the cracks in broken pavement blocks, her photographs penetrate the quotidian. In a sense, to be penetrated means to allow things to enter a world; in order for that to happen, that world needs to be fragile. Yet, as Kawauchi reveals to us, fragility is already intrinsic to our world. Eventually, the awareness of fragility means susceptibility to the realm of interpenetration suppressed within everyday human life.