The portraits amount, at first glance, to a poignant memorial, honoring the grace and brio of a mother who dominates most every frame. But they also literalize the artist’s mission to situate herself within a complex political history. Kganye’s reënactments of the family scrapbook took her across the country, to visit uprooted relatives who, along with millions of black South Africans in the second half of the twentieth century, had resettled in response to apartheid-era policies of forced removal. Her larger project, which includes oral histories from these relatives, constitutes not simply a celebration of heritage but a fraught autobiography. One of Kganye’s most pressing questions concerns the spelling of her surname, which appears in several variations on the birth certificates of her forebears—presumably modified by the relatives themselves, in an attempt to assimilate, or else warped by negligent law officials, in the updates of government ledgers. Apartheid cleaved countless fathers from their families, forcing men from rural households to the cities in which they toiled as migrant laborers. Kganye’s grandmother raised six children alone until they were able to join her husband, Kganye’s grandfather, in the city; Kganye’s own mother was also a single parent, and “Ke Lefa Laka” doubles as an ode to the miracles of matriarchy, linking the artist to her past through generations of women.

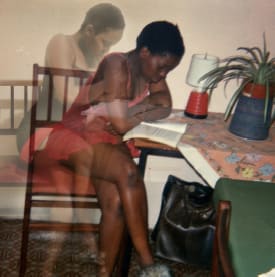

Kganye has characterized her series as an attempt to replenish the “paucity of memory” by injecting her living image into visual records of the dead. Her inspiration was, in part, the work of Roland Barthes, whose slim but ambitious book “Camera Lucida” serves at once as a eulogy to his late mother and an attempt to innovate new modes of observation. In her artist’s statement, Kganye writes of her own mother, “She is me, I am her, and there remains in this commonality so much difference, and so much distance in space and time.” A few images feature Kganye as a wide-eyed, ebullient baby, celebrating her first birthday or tottering across a lawn. The artist appears twice in these frames, once as an infant and then as an older apparition, lifting a glass to her lips or cheering on her own first steps. Placed beside the parent she has lost, Kganye appears to yield to a peace on the flip side of grief. She mourns her mother by mothering herself.