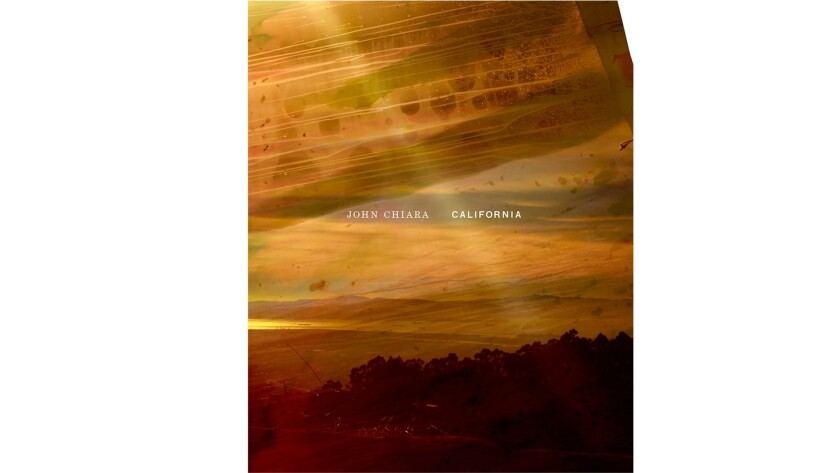

Photographing California with a camera as big as a truck

“North Harbor Drive at Marina Way, Redondo Beach,” 2013; from “John Chiara: California”

The most ubiquitous camera in use today, the iPhone, fits inside of our pockets. The largest of artist John Chiara’s cameras, on the other hand, is big enough for him to step inside.

Transported on a flatbed trailer, that camera takes photographs the analog way; his book “John Chiara: California” presents a collection of these idiosyncratic images made in his home state.

Chiara built his first large-format camera in 1997. He wanted “a certain type of image that wasn’t available through commercial cameras, so I had to develop my own,” he told The Times. Instead of film, he uses large sheets of photographic paper that he exposes through a lens opposite — like a camera obscura, or a huge pinhole camera, or a large daguerrotype without sheets of glass.

Chiara’s custom cameras produce landscape and architecture photographs that exist outside of the realm of crystal-clear digital photography, and stress the art of process.

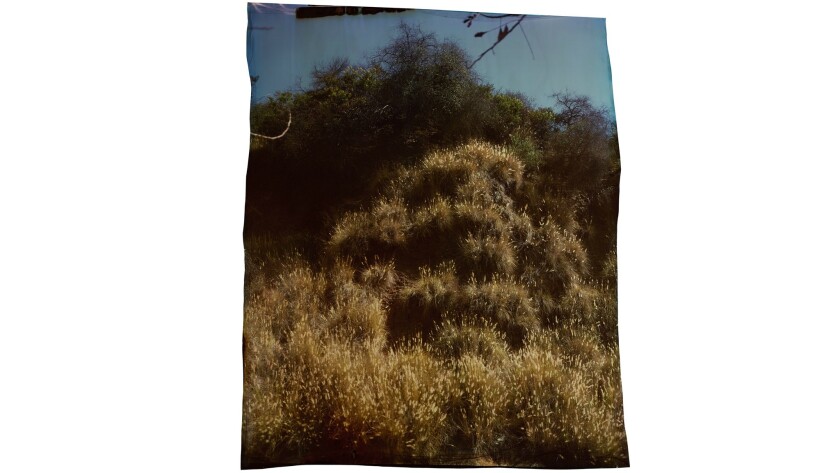

“Western Canyon Road at Mount Hollywood Drive, Los Angeles,” 2013; from “John Chiara: California"

“It’s a different type of image that has a lot of the noise from the process, and from the camera and from the development,” he said, referencing “the drips from the chemicals and the tape that’s left on at the bottom” as examples of that visual “noise.”

Striation across a burst of bougainvillea draws attention to itself, reminding the viewer of the work and chemistry that went into creating it. The edges of the photographs are slightly wavy and uneven, an indication that the photographic paper is a physical thing that can twist and buckle. Among the pleasures of these photographs are their nuance and individuality. Unlike a film negative or a digital image that can be printed in many multiples, his photographs exist only in their original form (and the images that are taken of them, like this book).

Chiara’s process takes time, from scouting to developing. “I have to go and really spend time someplace before the work starts really happening,” he said. “It’s a matter for going out and really looking.” In conversation, he refers to the experience of shooting as an “event.”

“We were photographing the glare coming off the ocean recently in California,” he said of himself and an assistant. “That had a much shorter exposure because of how bright it was, so that was a minute and a half. Normally it’s 10 to 15 minutes.” He enjoys the anticipation, revelation and discovery.

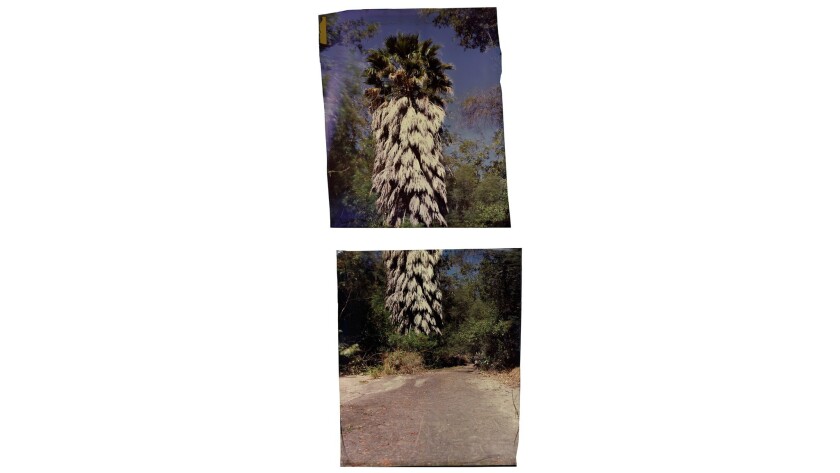

“Topanga Canyon Boulevard at Pacific Coast Highway, Los Angeles,” 2012; from “John Chiara: California”

The book itself took time to develop; the photographs in “California” span 18 years and were shot across the state, in San Francisco, Nevada City, L.A. and elsewhere, imparting the loose framework of a road trip.

In her essay for the book, Virginia Heckert, head of the department of photographs at the Getty Museum, writes that when photographing Los Angeles, Chiara took full use of “the expressive qualities of the vertical diptych, most notably to encompass the full height of the city’s ubiquitous but varied species of palm trees. The staggered effect of stacked panels more closely approximates the way we take in our surroundings than a single image can.” There were other technical challenges particular to the city: Because of the film industry, shooting permits are stricter and include an enormous still camera being towed around on a flatbed behind a truck. “What if I just had a regular camera? Or what if I had a canvas and was painting,” Chiara said and laughed. “Would I need a permit for that?”

“Chiara… does not strive for the same kind of picture-perfect, postcard scenes that have come to color our experience of many of these sites even before we visit them,” Heckert writes of his departure from the ubiquitous commercial images of California. In describing his subject, Chiara echoed her sentiment. “I very much am interested in the history of this region and the photography that’s been produced here,” he said.

“North Harbor Drive at Herondo Street, Redondo Beach,” 2013; from “John Chiara: California”

His photographs of Los Angeles — slightly washed out, sun bleached — are stark and familiar. They look the way that L.A. feels, like a heat wave mid-September, or the moment before your eyes adjust after taking off a pair of sunglasses. Other images, of different towns and regions, verge on the abstract.

For Chiara, the photographs in the book contain a “slight diary aspect,” but his ambition is more outward-facing. He hopes that for the viewer, “the work can touch on a collective memory of place.”

“Vereda De La Montura at Camino De Yatasto, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles,” 2013; from “John Chiara: California”

“John Chiara: California” (Aperture/Pier 24 Photography )