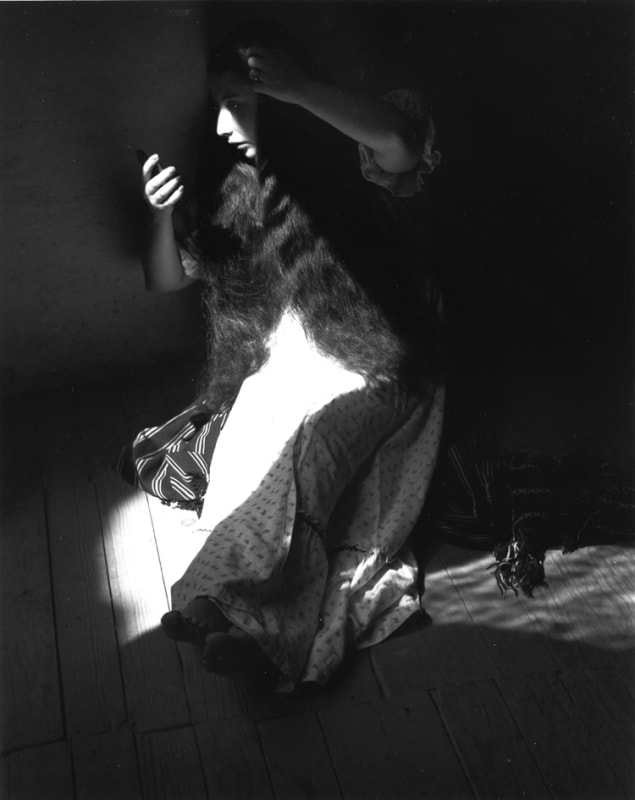

AMONG THE WORKS of Mexican photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo is an image made in 1935 of a young woman seated in half shadow, wearing a dressing gown and striped shawl. Intruding through an unseen window is a prism of light, whose shape forms an uncanny, expanding echo of her profile. As she pulls back her long, shimmering hair, she stares into a pocket mirror. In it, she can see what she obviously already knows: that she is extraordinarily beautiful. Something else is also obvious. Her beauty terrifies her.