Callis has been in the news for the 2014 publication of Other Rooms, an anthology of what she had originally called her fetish photographs from the mid-1970s, now sumptuously printed by Aperture with an introductory essay by Francine Prose. The work garnered much praise and raised some eyebrows. Callis’s sensibility might be described as a heady blend of the mischievous and the prim. At the Museum, she said of one of her photographs that “it looks like a bordello to me. Or what I imagine a bordello to be like.” Up till now, most people had thought of Callis’s oeuvre as being both elegant and mysterious, characterized by sparse, finely-staged photographs of rooms subject to questionable degrees of order and human control. In the title picture to her 1999 exhibition at the Getty “Woman Twirling” (1985), a woman spins close to the corner of a nearly empty room. She is little more than a skirt and a blur. In the foreground, a lamp sits on a small round table, its base made of carved wood, depicting a couple melting into each other in an embrace. While the twirling woman might be celebrating, she seems in a frenzy. In her Museum talk, Callis calls attention to her “repetitive action”: this, she says, is a sort of “madness.” What exactly are we witnessing? Like a lot of Callis’s images, it borders on the political, raising questions about women’s roles in our culture and their responses to those roles. And like a lot of her images, it shares some of the wild logic of a dream. But if so, whose?

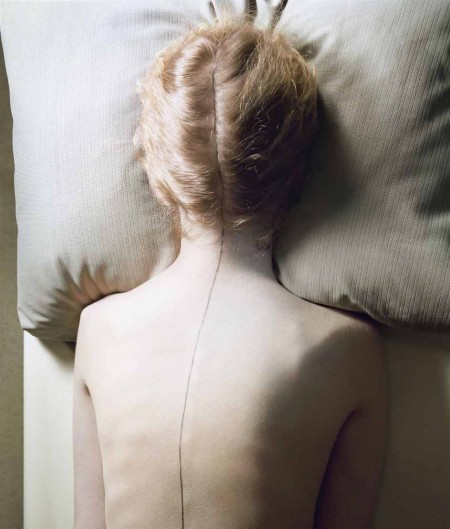

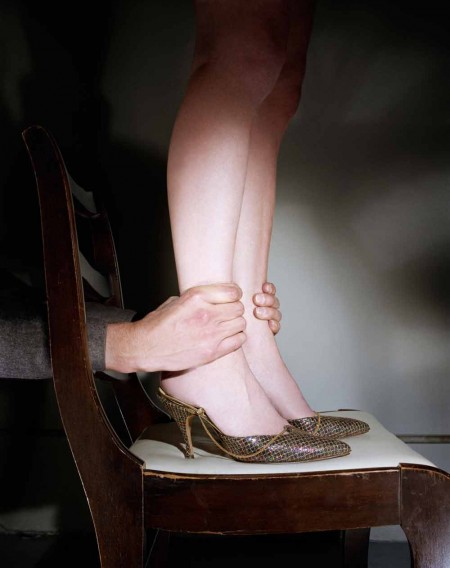

Francine Prose, in her excellent introductory essay to Other Rooms, observes that Callis’s photographs are “rich in erotic possibilities,” though it is worth noting that this is not quite the same as saying that they are richly erotic. The pictures are smart and telling, but they are certainly not depictions of—or incitements to—pleasure. In speaking of her work, Callis begins by asserting her formalist credentials: “I wanted my pictures to be constructed formally, and to be kind of tight.” Francine Prose wonders “what is so erotic” about these photographs? What “about a dark line, like the seam of an old-fashioned stocking, drawn from the top of a woman’s head straight down the length of her spine?” Prose’s answer begins with imagining the sort of scenario of sexual play that produces such a mark: “it’s something the woman is unlikely to be able to do on her own….We wonder: at what point does a lover feel comfortable enough to say, Want to know what I really like?…At what point in the discovery of desire does a woman realize that is what she wants?” Callis explains a different sort of origin for the picture: “It started with the feeling of a bowling bowl on a pillow.” In describing “Hands on Ankles,” Prose asks “How many of us could have predicted that a pair of hands, grasping a woman’s ankles, could be as charged with emotion as hands joined in prayer, in this case before the altar of the woman’s shoes?” Callis explained that she was drawn to “the way the heels dug into the chair.” She values “that moment of a little tension” because “the hands make it precarious,” and then noted “I felt the shadows were good.” She is perhaps the opposite of another photographic formalist of the 1970s, Robert Mapplethorpe, who sought prurience everywhere but actually captured it only fitfully; Callis was uninterested in prurience and found signs of it all over.

Callis’s photographs are psychologically rich in many ways, but they do not particularly depict people: “I didn’t want to make pictures about personalities.” She notes how rarely she has photographed human physiognomy: “I never got around to it. What would I bring to it?” She is proud that her aesthetic leans towards the artificial. “I never made a documentary photograph or a nature photograph,” she told the Museum crowd; “I never wanted to go out into the world and take a picture of what was there.” With the opposite sensibility from a street photographer, her work has roots in the artistic traditions that bring things into the studio rather than those that can be found outside it. This includes the still life, which she has thought about a great deal. She explained that her work—which includes an elaborate series of desserts posed on fabric—updates the still life tradition, though still honoring its roots in the French term for it, “nature morte”: “The still life represents death. All photographs represent time passing.” The still life also has its roots in the celebration of privilege: “Those things in the classical still life were included to show wealth, to call attention to a kind of rarity.” But that rarity means less now. “You can get anything you want now. Take a melon, for example. Now, anyone can have one. It doesn’t mean anything.” What Callis values in still life starts with the attention to the tangible: “You look at objects lovingly, putting a light on them.” At the core of her work was a central decision: “I went back to the love of objects,” and then to place them into the right sort of context. The work, for her, “would be fun. You know, like putting an éclair on fur.” There is part of her work that regularly (and elegantly) performs things for which a child would be scolded.

“It was fun,” she explains, “to set the stage.” In some ways, in her work she functions as a Hollywood set dresser might, and specificity is essential to the art of getting such things exactly right. She points the Museum audience to one of her photographs and notes “those are the 50s colors, right? Look at the pillows. It’s very 50s, even though it was done much later.” She thinks of her work, in part, in cinematic terms. “I wanted to use shadows. I loved all that film noir.” She tells a story about her brief association with the classic 1980 neo-noir movie, American Gigolo, while it was being filmed. “I got an invitation to visit the set because in one scene, a picture of mine was leaning up against the wall. I got to see Lauren Hutton and Richard Gere in bed.” But the experience was for her not about being star-struck but about the movie’s made environment. “I thought, Oh my God, if I had that budget! Mine is so rinky-dink by comparison.” It was right around this time that she got the work space—and play space—that she needed: “I didn’t have a studio—a garage of my own—until 1980,” and with that space, “I could make an environment that would speak what I wanted it to do.”

Callis’s relationship to the narrative aspects of her work is complicated. In some interviews, she has talked about the narrative elements to her work; in others, she has said that “nothing is really happening in the photographs.” I think that she tends to think that witnessing a story being told (or hinted at) keeps her audience outside the drama; in her mind, the important thing is to be enabled to enter into the story yourself. When asked, for example, about the relationship between her photographs and the dramatic, if toxic, settings for film noir, she says: “Film noir. That’s what I saw growing up. The movies were too scary, but I remember from seeing them that you can hear the footsteps. The sets are fabulous. But those footsteps….I can remember just listening to that as a kid, all the tropes with the sound a woman’s high heels on the floor, the noise of her shoes. I can hear that in the sound of my own shoes, walking down a hall.” The key is not to crowd out the sensibilities of the audience. When asked whether she’d have liked to photograph a strange collections of objects in some shop window, she said no. “They’re not generic enough. You can’t fantasize about them.” The importance of her carefully chosen assemblages of objects is that they “set the stage for the mind to go elsewhere.”

If there are stories in her photographs, they are evoked—they are provoked—by things. Mise-en-scene is everything. “Everything speaks,” Callis says. “You communicate a lot by the objects you choose. Picture the house you grew up in. All the places I’ve lived, I remember them, the feelings I had about them. I looked at those rooms and I thought, ‘There’s my life.’ What we thought was good taste—the overstuffed couches of shabby chic—I look at them now, such droopy stuff.” Thinking of an example, she finds herself playing a role suggested by the setting in which she finds herself. “Take my hotel room. It’s simple and it’s elegant and it makes me feel rich.” When asked about the sources of these impulses, she is taken back to the roots of most people’s domestic sensibility. “I think it’s my Mom. She loved beautiful things. We didn’t have a lot. I remember going shopping with her and she’d say, ‘Feel this fabric.’” The well-curated object becomes Kane’s sled, Proust’s madeleine. Callis’s assemblages of things are rich in skewed meanings, like the stable iconography of a medieval altarpiece seen freshly by surrealists, guided by—and guided to—memory. When a catalogue of her Selected Photographs, 1977-1989 was published, its title was Objects of Reverie. The focus is on the objects, not the reveries, and not even on the dreamer. “We come and we go,” Callis observes, “but our things last.”

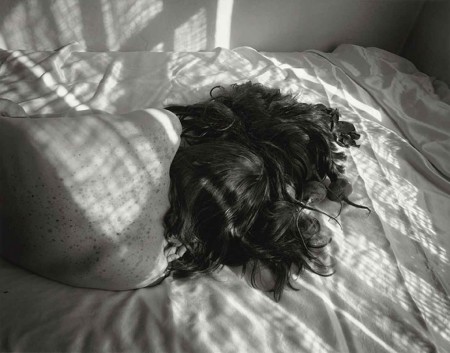

There is a generosity to things in her world because of the ease with which they become part of the backdrop for an enchanted rehearsal space. When she was told about the physical arrangements for her Museum talk, the scene came alive to her. “We’d have two upholstered chairs and I immediately got an image. Yellow is fine, and I’m wearing gray. That’s where my mind goes all the time. Color affects us.” It’s not a long step from there to the sorts of eros she creates in the photographs of Other Rooms. “To sit naked on an upholstered couch,” she pondered with the Museum audience, “that would be…somewhat odd.” She explains that “I don’t have real stories. If you set the stage well enough, you will communicate something.” In her introduction to Other Rooms, Francine Prose brilliantly imagines stories behind the photographs. Typically, there is a woman and there is a man. “At least two people are involved. Which or both of them wanted to know how duct tape looked and felt against the flesh?” But Prose seems even more on target when she imagines the underlying erotic scenarios as less deliberate and less interpersonal, fantasies that are more happenstance and solitary: “Callis’s images catch those moments when the mind drifts to thoughts of sex, while we are doing something else: buying groceries, standing in line at the bank, crossing the street, trying to fall asleep.”

Jo Ann Callis, “Woman in Crimson Slip” (1978)

The richness of Callis’s best photographs throughout her career comes from her sharp understanding of our double-mindedness. We can appreciate the mysterious and the banal at the same time; we are at home with moments of emotional intensity masked by emotional casualness. In “Woman in Crimson Slip” (1978), a faceless woman has raised her red hem to shine a penlight on her inner thigh. It means something; it means nothing. It focuses our attention in a way that is sexual or medical or cinematic or obsessive or childlike. Either way, if you open your eyes and open your mind, memories, strangeness, and sensuality may come flooding in. And when that happens, you go with it, and try on for size what is being offered. As she told her audience at the Museum, “If I get new ideas, it’s a gift, and I’m going to take them.”

–Jonathan Kamholtz