Whether sculpted with the camera, clay or oil, Jo Ann Callis has a way of transforming seemingly ordinary objects in an extraordinary way, of turning the psyche inside out for provocation. Her carefully crafted, suggestive scenes permeate your skin and travel to the most intimate “room[s] in your mind.”(JAC) Seeing Jo Ann’s work for the first time, gave me the confidence to explore my own life in all its complexities through constructed photographic narratives and to not be afraid of theatricality that I’m drawn to. I’m so grateful to have her as a mentor at CalArts and to now call her a friend. She is a continuous source of inspiration and support. We spoke earlier this month at Jo Ann’s home in Culver City where she talked openly about her life, process, and preparation for her second-solo exhibition, Now and Then, at ROSEGALLERY in Santa Monica, which opens on the 18th of next month. Her work can also be seen in “How They Ran,” a group exhibition that recently opened at Over The Influence Gallery in downtown Los Angeles.

Her new work looks to connect the past and present historically and socially where previously her connection was primarily personal. This slight shift allows her to be both conceptual and socially conscious during this radically political time. After years of working in publishing at the Los Angeles Times and animation at Nickelodeon while holding her photographic self tucked away in a (locket), it wasn’t until experiencing the death of both of her parents within a four year time span that she began pursuing her artistic practice full-time. She is currently in her final year of completing her degree at CalArts.

Jo Ann Callis was born in Cincinnati, OH and relocated to Los Angeles in 1961. She enrolled at UCLA in 1970 where she began taking classes with Robert Heinecken, among other prominent artists. She started teaching at CalArts in 1976 and remains a faculty member of the School of Art’s Program in Photography and Media. She has continued to photograph, draw, and paint, and her work has been widely exhibited in such venues as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Hammer Museum; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and many others. In 2009 a retrospective of her work, Woman Twirling, was presented by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Callis has received three NEA Fellowships and a Guggenheim Fellowship, among other awards and prizes.

Brandy Trigueros: Can you describe your childhood home and growing up in Cincinnati?

Jo Ann Callis: It’s funny you brought that up because I was thinking about that today, since I had guests over last night and we were remembering things from the past that have changed. We were talking about how much and how fast the world has changed with the advent of digital technology. In reminiscing about the past, I was picturing my home and how much I loved our house. I loved the way my mother decorated it, her style in decor and clothing influenced me. The world outside was a bit scary to a young impressionable child, especially school, which I never really liked but I felt very comforted and safe by being at home. The domestic domain is still relevant to my art.

BT: Is there a particular art piece that moved you at an early age to become an artist?

JAC: Not really but I loved making things and I was praised for it. When I was about 8, I was looking at an art book my parents owned and I saw a drawing of a nude woman. That made an impression on me because it seemed like such a daring thing to see: a nude woman reproduced right on the page of a book. It was possibly from the Renaissance period, I don’t know who the artist was but I thought it was so beautiful. I then took classes at the Art Academy and made little clay things. I think I just always gravitated to the arts because it made me feel good. Just going into the art studio – the smell of it, the activity of art making, the tools, the people, it was an exciting place to be. In high school, we had an art room and of course that was the only class I really loved. Then in college, I went to Ohio State for a couple years, which had a very old building with wonderful Roman arches and the whole building was steeped in art.

Woman with Black Line, 1976-77. From the Early Color Portfolio © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: When we first met at CalArts, I was nervous albeit excited at the possibility of mentoring with you. I remember one of the first questions you asked me was my age. I know we share a commonality since you were also in your 30s when you returned to school. However, you were juggling the demands of college while simultaneously caring for two young children. How did you manage it? How has motherhood influenced your work?

JAC: I did have a little help in the house when I went back to school that I hadn’t had before, which allowed me to go to classes and study; it was very liberating, but I remember I had to juggle a lot with a family, school and making art. As a mother and artist my studio has always been at home, first by necessity and then after my children were grown, I just continued to work that way. Not only was it convenient but I also got used to working at home where I could go in and out while juggling everything else. Which is still the case with my home studio.

Hand in Honey, 1976-77. From the Early Color Portfolio © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: Is there anything you feel you gained or lost being a more mature student?

JAC: I think I was more motivated, but I also felt I was ten years behind and needed to catch up. Although in grad school people at UCLA were very good artists and were always engaged, so I felt the tough competition even then. Art meant everything to me. I just had to figure out a way to make a living and to exist on my own, I couldn’t think of anything else I could do. I’d ask people all the time, “what do you do?” Then a teaching opportunity at CalArts came up and thank goodness I got the job. I had never taught before or even wanted to teach, but it gave me a way to make a living in the field I loved. At first I was petrified but I took the job out of necessity. I have been there for 42 years. I’ve met a lot of wonderful people through teaching and that is the best part of doing it.

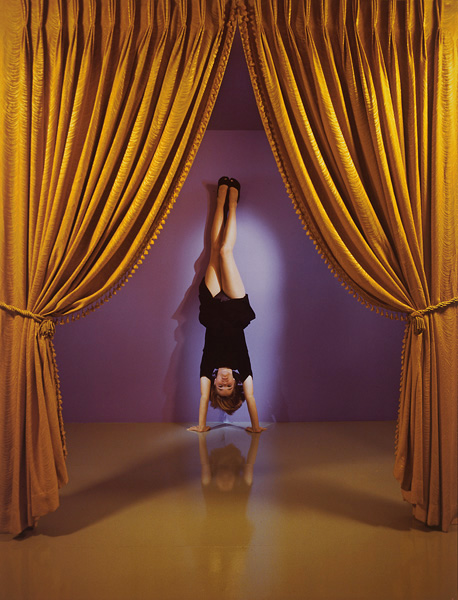

Performance, 1985 © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: Since you studied with Robert Heinecken at UCLA, have you utilized any of his teaching methods or passed on any of his particular pearls of wisdom as a teacher and mentor at CalArts?

JAC: I tried to mimic Heinecken, because he was a great teacher. I even asked him for his notes on teaching which he gave me, but they weren’t formal notes and nobody can really teach like someone else. The main thing I’ve utilized is to focus and praise what is good and to say why an art piece is working and why it isn’t working. I always saw how kind he was. Sometimes he would look at photographs at workshops and I would wonder what he was going to say about them. I thought some were not very good and yet, he would be so kind and find things in the work to talk about that would help the workshop participants. He was so helpful. Personally, I received a lot of support from him and that really gave me the confidence to continue in photography. That’s what I’d like to pass on to students: I want to help them find their own voice and to love art as much as I do.

BT: When you were starting your career, do you feel a woman’s gaze was accepted or taken seriously?

JAC: When I was starting my studies nobody talked about that very much and then everything changed when we started deconstructing photographs; feminism influenced everything, including raising consciousness in art. I was not very aware of the objectification of women. The models in my photographs were surrogates for myself. In the late ‘70s, at the Regional SPE conference, which everybody used to go to at that time, a feminist hissed at my work because I cropped the head of women in my photographs. I wanted it to be any‘body’ – any person. Sometimes there’s a face but I didn’t think about whether or not there was a face, I just knew it looked right. It was about the gesture of the body or body language or how it was relating to the objects around it and the environment, not about features or the personality of the model.

Applying Lipstick, 1976-77 © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: Can you describe your art-making methodology? Do you keep a journal of memories, secrets and sketches that are later revealed photographically or sculpturally?

JAC: I used to sketch but it was never in a journal, it would be all over the place, on napkins and such. David (Jo Ann’s husband) and I used to go out for a drink, talk about art ideas and sketch things. I would make a little thumbnail sketch and then write a prop list prior to photographing.

BT: Has your working method evolved in some way over the years?

JAC: I’m not photographing now like I used to but I’ve been making sculptural pieces. I’ll do some initial sketches of what I think they might look like, as a place to start but then when I get into the clay they completely change. I think to myself, that doesn’t look good, so I’ll turn it on its side and push into it and then ah, that looks better. It’s so malleable, I can’t really plan too much and they are somewhat abstract, with figurative overtones. When I make photographs, I always set things up first and make sketches.

Woman Twirling, 1985 © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: So sculpture is dictating much of your work now?

JAC: Yes. I’ve made sculptures before and then I used them in photographs, sometimes they were shown on their own. It’s interesting that in reviewing photographs I made many years ago for my upcoming show at ROSEGALLERY, I have a distance from them because they were made 40 years ago. I don’t feel so vulnerable about showing them since I’m more detached, which makes everything so much easier. I am not so sensitive about them anymore. Also, as much as I personally don’t like to use digital technology, I depend on my printer, Evans Wittenberg, who is an artist himself. He understands what I want and we talk the same language. He knows how I want things to look, so when we work together I feel like I’m making a new picture. They’re just different enough to make them feel new to me. With so many more tools at our disposal now, the pieces I might have rejected in the past because they didn’t do enough for me at the time came to life through a new printing. It might be the same imagery but it feels very different. It feels more emotionally true, more what I wanted it to be in the first place. Therefore, I do feel like I’m making new work when I made these new prints recently.

BT: I’m going to share a secret with you in hopes you’ll share one with me. In my preadolescent years, after watching too many episodes of Murder She Wrote and reading borrowed Nancy Drew novels from my mother, I started a spy club of sorts with a few of my closest girlfriends. It all began innocently enough but to try to make a long story short, on one occasion I peeped into a neighbors window and it’s as if a Jo Ann Callis scene was unfolding. Do you feel your work, particularly your more sexually explicit early color portfolio, calls attention to the spectator and voyeuristic tendencies most of us carry/hide?

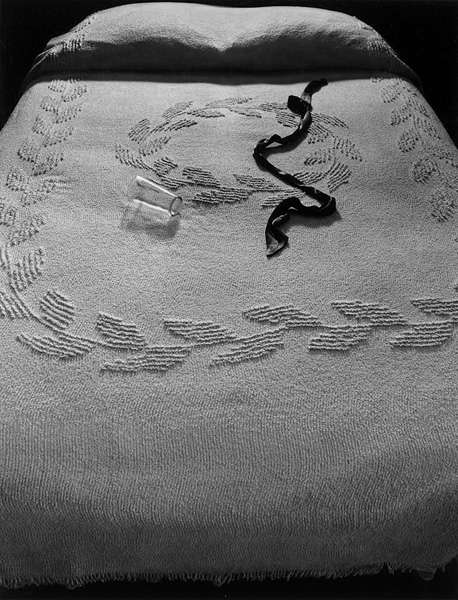

JAC: If not literally, it takes you to that place of voyeurism, of what seems forbidden, more of a feeling rather than anything literal. Sometimes I used to vignette my prints so it felt like you were looking through a peephole. With straight photography, the camera is recording what’s in front of it given the light and so the challenge was how to use a medium that has so much veracity and make it metaphoric, so the meaning isn’t exactly what you’re literally seeing. It’s a feeling of that space or a place in your mind. How do you photograph an interior feeling, a mental place? That was a challenge for me with those pictures. Objects and their meanings in the culture were also important. In early still life paintings, we would see beautiful fruits and glistening glasses filled with wine, but all those objects held meanings that were different from today, such as their rarity, after all, how did one easily get a grape in the middle of winter? Making still life photographs, which always interested me, allowed me to work without depending on anyone else. With models, there was always the probability of having to reshoot it to get it just right. It seemed I would rarely get it on the first round. I loved making both kinds of pictures.

BT: Do you believe your work is in some way acts of rebellion or is it psychologically driven interior states of mind? Or both?

JAC: I wouldn’t say rebellion, I never thought I was being rebellious. I just wanted to make the work I was interested in making. When I learned photography it was a time when everything seemed so liberating. Sexual liberation was openly expressed everywhere. It was in everything: the clothing or lack thereof, in free love, in communes, and in art. The ‘60s and ‘70s had arrived! Those liberating times affected everyone but for me it was also the anxiety of living that I was feeling because I wanted to get out of my marriage and was worried about how I was going to support myself. Then when I was divorced in 1975 all those factors played into my art. This whole new world opened up, there was a kind of freedom and experimentation in the air. There seemed to be fewer taboos at the time and the buttoned up 1950s had passed.

Man Standing on Bed, 1976-77 © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

Untitled (Yellow Bed, Pink Floor), 1995. From the Domestic Interior series © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: How do you access or find the creative energy to make-work when you’re feeling uninspired? Is there a particular movie, music, artist, or person that helps open up the floodgate?

JAC: If I’m really down, it’s very hard. However, when I go to exhibitions and look at art, from any era, I find if something speaks to me, I get really excited to make art. But if I can’t focus or when I feel like my mind is everywhere, that’s sort of where the clay comes into play. I’m not thinking of anything technical in making those forms. If I had a full-time assistant, I would probably be photographing more, but right now, I really do love making my sculptures. I feel I can express my humor, sexuality, and sensuality with these abstractions. It’s where I started, as an art major at Ohio State in 1958 I gravitated towards sculpture. Making dimensional objects can be problematic in a practical sense, because if they’re large pieces, there’s nowhere to store them. I threw out so much because there was just nowhere to store them. Now I’m back to making small clay sculptures and that gives me great pleasure at the moment. I can form them relatively quickly which is quite satisfying, but of course finishing them is time consuming. I would love to try casting my new pieces into silicone. I think the material itself would be so beautiful because the light could come through it – they would be translucent.

BT: Will we get to see some of these new sculptural pieces in your upcoming solo exhibition next month at ROSEGALLERY in Santa Monica?

JAC: Yes, there will be 6 or possibly 8 small sculptures that are kind of sensually suggestive of the body but not explicit in any way. They are tactile since they’ve got beeswax covering their surfaces. The process is really fun and that’s what I want to feel while making my art these days. I want it to feel like play.

Doughnut, #12, 1993-94. From Cheap Thrills and Forbidden Pleasures © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: What achievement, artistic or otherwise, are you most proud of?

JAC: Being older and still wanting to engage with art passionately is a success for me. It saved my life, so to speak, and still gives it meaning. I don’t have to retire from anything; art is just a part of me that feeds my imagination and gives me pleasure.

Jayne Mansfield, #8, 1993. From Cheap Thrills and Forbidden Pleasures © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)

BT: What do you consider success? What’s next for someone who has had an exhibition of their work at the Getty?

JAC: I don’t think in terms of goals at all or what’s next. I never really did. My goal all along was to keep being an artist, and I met that goal. I just want to keep making work if it still feels good to do that. I would consider that a successful life along with having the love of family and friends. Those are the things that are central to my feeling of well-being. I think I have been very lucky since it’s all about the journey, right?

BT: I couldn’t agree more.

Dish Trick, 1985 © Jo Ann Callis (Images courtesy of the artist and ROSEGALLERY)