Dirk Braeckman: Capturing Quietness

When Dirk Braeckman began studying photography and film at the Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent, Belgium, in 1977, it was with the intention to become a painter.

With artists such as Gerhard Richter using layers of paint and photorealism to interrogate representation, Braeckman initially saw photography as a tool towards the painterly. Yet, upon entering the darkroom during his first year of studies, Braeckman was transfixed by the alchemy of the analogue process and has worked in the format ever since. Rather than documenting or telling stories, his photographs embody the mystery of the darkroom process. Non-places—such as hotel corridors and rooms, a window frame or curtain—are printed in monumental portrait scale on matte paper, their surfaces sometimes interrupted with light glares, spotting, and other textures that reveal the hand of the artist. Nothing is revealed, however, of the settings in which Braeckman captures these photographs, and there is a quietness to their anonymity.

Dirk Braeckman, R.D.-B.R.-20 (2021). Ultrachrome inkjet print on matte paper (edition 1/5) (edition of 5 + 1AP). 90 x 60 cm. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp.

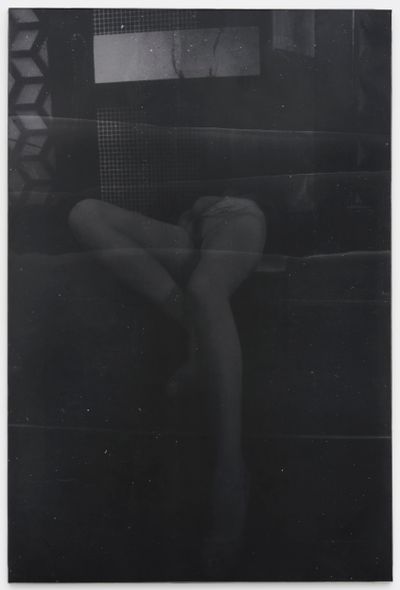

Dirk Braeckman, B.I.-B.I.-17 (2017). Gelatin silver print. 180 x 120 cm. © Dirk Braeckman. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp.

For the artist's upcoming exhibition at Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp (10 March–24 April 2021), images have been selected from this archive under the title FERNWEH—a German word that translates literally to 'distance-pain', and describes the longing to travel far from home, to new places. The exhibition is a snapshot into his archive, where the artist has spent more time than usual during the covid-19 pandemic, and offers a glimpse into the trajectory of his practice, including recent experiments with landscape photography and colour. In the lead-up to the show, we sat down to chat about such developments within the arc of his practice.

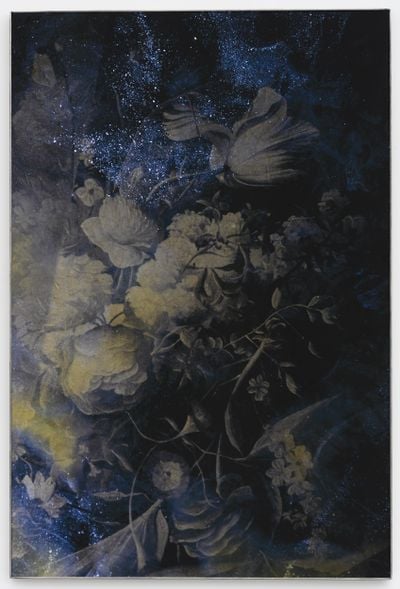

Dirk Braeckman, Fernweh (2021). Ultrachrome inkjet print on matte paper (edition 1/5) (edition of 5 + 1AP). 120 x 80 cm. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp.

I wanted to start with your beginnings in photography. Your practice in the darkroom is frequently approximated to that of a painter in their studio. Were you painting before taking photographs?

My best friend when I was about 10 or 12 was a gifted drawer and painter—he influenced my interest in painting. Through him, I made contact with older, local painters, who I spent a lot of time with. Before I went to the Koninklijke Academie, I had been assisting some of them. They were not well known in the art world, only in smaller, local circles, but they were good. At 18, my friend died in a fire, and I felt I needed to continue that dialogue around art with him. He introduced me to the joy of painting; it wasn't just about painting an image, but how those images were made. When I was young, my parents took me to museums, and I remember standing in front of L'Origine du monde by Courbet, admiring the traces of brushstrokes.

I went to the academy with the intention to study painting. At that time, painters such as Gerhard Richter were using photography to make their paintings. Richter has a huge collection of photographs from which he works. I was talking about that with my friends, and it occurred to me that I could study photography first, for a few months or a year, before painting; but in the end, I never left it. I was so impressed by the darkroom process, and I'm still impressed with the atmosphere of the darkroom, 40 years later. When I work in there, I try to find new challenges, so I can experiment with the same kind of mystery.

And the mystery has continued.

Yes, it never stops. It challenges me all the time.

Before you began in the darkroom, you were a photographer surrounded by painters, essentially.

Painters and writers, but no photographers. When I went to the academy, the professor asked me what kind of camera I used, and I said, I have no camera! And then they were surprised I wanted to study photography.

I realised very quickly that I was not made to do documentary photography. I wanted to create images, not tell stories about certain events or places. I just needed an image from a certain reality, a little bit like a painter who makes photographs and brings them back to the studio, and then makes a painting of that basic image. In the 1990s, I went to New York for three months. I went out walking in the streets, and because I was kind of shy I started photographing things around me, rather than people. That's when the shift away from portraiture happened. Another thing that influenced me was a photobook by Luc Sante, called Evidence (1992). He made a book about crime scenes from the 1930s, where the body—the subject—is absent. They're suggestive images.

Time is an important aspect of your practice, particularly in the lapse between shooting the image and then selecting it from your archive. You have been quoted saying that you are 'driven by the desire to give order to chaos', yet you refuse order, in that you go back and forth in time when selecting images from your archive.

It can be reordered all the time. The reason why I take time to select the images is to create an emotional distance from the moment I shot the image. When I have some time and distance, I can focus on the content of the image. Sometimes I don't remember where I shot it, but that leads to a new discovery. And I like that—to discover something that I forgot about.

While the photographs may exist online and in books, how important is it for you that they are seen in physical space?

In my case, it's very important to see them in real space. Of course, every artwork needs to be seen in person. When you see a painting or sculpture in a book, there is a tactility or a certain scale missing, but with a photograph, you just read it as a photograph. That's why in my work it is very important to see it in physical space. People sometimes say they don't like the images because they're photographs of ordinary things, such as curtains, but sometimes those same people will go to a show and come back and say, 'Now we get it!' The physical approach is so important.

By physical approach, do you mean the physical approach in the darkroom?

That's also important. I built a huge darkroom, and the first investment was a very good ventilation system so that I could stay there for long periods at a time, and enough light to see what I'm doing and to be able to work like a painter in their studio.

Dirk Braeckman, X.C.-C.X.-20 (2021). Ultrachrome inkjet print on matte paper (edition 1/5) (edition of 5 + 1AP). 90 x 60 cm. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp.

Would you say that being in transit is fundamental to your practice as a way of embodying that fleetingness, of capturing and leaving moments behind as you move through space?

I don't go anywhere with the intent to take pictures. I travel to discover something, or for other reasons. Of course, I'm more surprised when I go to a place that I don't know, and there are more impulses that arise, so I shoot more. But I don't travel to shoot, and that's very important. Even when I am at home, I shoot my surroundings and archive the images. I use the reality that's around me to capture a state of mind. In some situations, there may be people around me. In the past, when I went to bars and clubs, instead of photographing the people around me, I looked at the décor. I wanted to capture a state of mind.

What are the aspects you are thinking about when putting a show together?

The reason why it's so important to install a show is the same reason as I said before: to see it in real space, and because the interactions between the images is so important. I never have a plan when I install a show. I do it when I arrive at the gallery, with the assistance of the team, because otherwise I am too emotionally close to the pictures. Sometimes I see connections that the public doesn't see, so I listen to others and we do it together. Because my works require so much physicality, it's very important how they are hung in space. It also depends on the space. One hanging might be completely different in another space.

How does that physicality feed into your more recent video work?

Actually, when I went to the academy, I studied both photography and film. At that time, you could choose a combination of photography and film or photography and design, and I chose the former. So I was also trained as a filmmaker, but I never used that because engaging a crew to make something was too complicated. It's not my style of working. But with the development of small digital cameras, I started filming on my own. The video works have been presented in shows, but like the photographs, they're not about stories, either. It's mostly it's about installation—for example, one of the last things I made was a video of a huge church bell (Hemony, 2012), which I filmed very close, but you don't hear the sound.

My goal in my work is to provoke sound-imagery—you don't hear it, but you can feel it. When viewers see my photographs, I hope that I give the impulse to other senses, not just the eyes; for example, when you see an interior, perhaps you can imagine how it would smell. Sometimes people say that they feel colour in the black-and-white photographs. You may recognise a texture so well that you fill it in with in your own colour, for example. That intrigues me. If a viewer can feel colour in black-and-white images, perhaps they can imagine smell, too, or a certain sound or texture.

In recent years, you have started photographing the landscape more, but not in the traditional sense. Images of the landscape are cropped a certain way to evoke a certain feeling.

There are many great landscape photographers, but in their case it's the beauty of the landscape that you see. I try to make my own beauty; to frame it in other ways, by using the portrait format, for example. The idea is to create another kind of landscape imagery, by focusing on details and creating a tension in the composition. When you see a perfect landscape, the tension is different. I try to put that tension in the beauty of the landscape.

Dirk Braeckman, F.W.-H.P.-21 (2021). Ultrachrome inkjet print on matte paper (edition 1/5) (edition of 5 + 1AP). 180 x 120 cm. Courtesy Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp.

Do you walk in the landscape?

Yes, more and more. Before, I lived in big cities, but I grew up in a small village in Belgium, where I played and worked on farms, so that's my roots, actually. And maybe I am coming back to it more and more, perhaps because I'm getting older, or because I am saturated by all the impulses that come with being in the city. But despite the quietness, the photographs are still loaded.

When the world opens up again, where would you like to go first?

I will be showing works in the São Paulo Biennial, so I hope I can go there. The show opens on 4 September